„The Family Archives” is a cycle of meetings with the inhabitants of Tomaszów Mazowiecki and its vicinities and an attempt to record their memories of once multicultural city. Family archives enriched with private stories serve as a way to organize past places and events and to restore former senses. Those dispersed narrations comprising personal experiences of storytellers are exposed to the lack of precision of dates or names, they create a panorama not only of real but also of imaginary events. It all makes these multithreaded narratives subjective, it gives them the shape of literary stained glass where one can find both real and fictional episodes. Shared conversations, walks, memories are a part of the project of saving memory of non-existent city, which once was a place of fusion of different cultures, including Jewish culture.

Everyone who would like to share the story of multicultural Tomaszów with us, please contact us at our e-mail address: fundacja.pasazepamieci@gmail.com or at our telephone +48 695 175 928. We present selected pieces of reportages, stories and interviews on our website. All writings will be published in form of a book. Project “The Family Archives” is the first project of the Spaces of Memory Foundation. It is ran voluntarily by Justyna Biernat and Bartłomiej Sęk, who wish to thank all their interlocutors for their time, precious stories and a will to share the past.

The story of an old chest

Closed in the ghetto, over fifteen thousand Jews were boxed in a small area. There was a hunger and difficult life conditions. From the beginnings of the ghetto my mum Julianna Sulmowska delivered food to this separated “quarter”. The recipient was a Jewish family, friends of my mum. From her stories we knew, that it was a tailor, his wife, seventeen-year-old son (mum didn’t say how many more children they had). It was better not to know too much about the ghetto, and using names and surnames was inadvisable. In case of being caught by Germans it could ended tragically. Entering the ghetto meant a death threat to the whole family. However mum risked every second day, until 31 October 1942. The day before two young women from Ludwików were shot to death next to the ghetto: Janina Hankiewiczowa (20 years old) and Janina Adamska (33 years old). At that time a troop of Lithuanian Szaulis came to Tomaszów to help protect the ghetto. There was no access to the ghetto. They shot to everyone who tried to approach. The ghetto was illuminated, and the city was dark. Often at night you could hear shots, one imprecise darkening of window, and they shot to that window directly. At the beginning of October, after coming back from the ghetto mum acted strangely, she had restrained moves. It turned out that she was enveloped with a piece of fabric. It repeated twice. We begged her and persuaded not to leave us orphans, because for contacts with ghetto she could get killed. She explained that she did that on a request of her Jewish friend and her husband – the tailor. “Dear Mrs. Sulimowska, we beg you to take and store these three pieces of fabric. We will not survive the ghetto for sure, but maybe our son will. He knows where you live, he will come to take these three pieces of fabric”. Mum said, that it’s not enough to make anything of it. “My son will make of these three pieces three pairs of trousers, sell it and buy fabric for four pairs. That’s how he will start his business”. After the war, against expectations, no one came for these three pieces of fabric. They lied in a drawer of an old, pre-war chest. In April 1945 my sister Eugenia came back, she was deported to dig trenches in Latvia and later in Lithuania. She had nothing to wear, she was poor, she asked mum to give her one piece of fabric for a skirt. Mum said: “Dear child, how could I look in the eyes of this boy if he came? You have to hold on”. My sister held on. The fabric lied in the chest until mum’s death. The owner didn’t come, most probably he died with his family, maybe in Bełżec or somewhere else. The chest doesn’t exist anymore, it was done in by the bark beetles, and the fabric by moths. According to the will of my mum Julianna Sulimowska they rest untouched. House at Niwka today is Kolejowa street. A new owner dismantled my old, beloved woodshed. Only memories left.

/author/ Tadeusz Sulmowski

/translation/ Katarzyna Danilewicz

She died so young

Last days of August 1941. Mum decided we needed things to school. We went to town. It was a beautiful, warm day. A bit tired (from Niwka, today it is Kolejowa street in Tomaszów),to the centre it was over three kilometres, “with a hook” as the highlanders say. I held my mum’s hand, Kościuszko square was empty, no vehicles there. When we were at the level of the statue of Tadeusz Kościuszko – not existent at that time, next to the clockmaker we heard a ramble. We slowed down and suddenly from around the corner of the square a gendarme occured, holding a pistol and putting it back to the holster. We felt weak at the knees and we didn’t know where to go next. Luckily the German entered the shop (today optician). In the meantime, from the side of the ghetto, four people ran pushing the trolley on two high wheels, followed by Jewish policemen. When we went round the corner, we saw a terrifying view. On the trolley there was a little girl, thirteen, maybe fourteen years old, lying, her arms hung inertly from the trolley. She was very slim, even skinny, dressed in a flowery dress. The Jews handling the trolley buried the blood. After a while they ran in the direction of the ghetto, to Polna street. Everything went smooth. The telephone from the killer worked well. Everything was back to normal. Except me and my mum, terrified, we went back home without shopping.

/author/ Tadeusz Sulmowski

/translation/ Katarzyna Danilewicz

I still remember

On the Kościuszko square, before the war, there used to be a turmoil, a lot of orthodox Jews with kippahs, payots, dressed in black. They sewed while-you-wait, they put out mirrors. There were also horseys and hackneys, when the carts drove the cart wheels rattled. On the market days mum traditionally used to buy me a halva. I remember those wonderful fairs with colorful merry-go-rounds, stalls, people dressed in their best clothes, in Białobrzegi. I remember the processions and traditional photographs taken by the photographer who had his fixed place next to the school, from the side of the church. I began my education with a delay. In 1940 in the school building for Polish children they established also a school for Germans. Very quickly I realized how the Polish-German integration looked like, when during the break, outside the building, I got punched in my face by a German from Ludwików, Maks. It was my first bloodshed. I was standing with my friend when he came and hit me. I fell down. I came home with swollen nose, I will never forget this. After that incident they told us to walk home in groups. It was supposed to increase our safety. Maks said that he made a mistake, someone else was to be the victim, not me. Later a company “Askania” settled in the school. We were kicked off and German kids went to school to Tomaszów. Us, in Białobrzegi or in Ludwików, we still went to learn, also in groups, so as not to get punched.

The whole war I wore wooden sole shoes, because my normal shoes broke. I was supposed to get new ones with the school kit, but we gave our savings to the Polish army for a machine gun. Germans occupied Poland and I found myself with wooden shoes and clothing made of felt, that’s how I got to the end of the war. First words I learned in German were “Herr Bitte Brot”. Once I was given a loaf of bread by Italian or Austrian, but then I think German supervisors from “Askania” noticed that. There was nothing to eat, so I know a taste of frozen potato. Frozen potatoes or carrots, I still remember this sweetness. Dad used to bike for food somewhere to Kraśnica, there he took some from barrows from a farm. Mum walked to Kraśnica or to Modrzewka, imagine that, it was thirty two miles. Most often she brought eggs, butter, cheese and poultry, they used to load her with wicker baskets. I have never thanked mum for that, I apologize.

/author/ Tadeusz Sulmowski

/editor/ Justyna Biernat

/translation/ Katarzyna Danilewicz

- Tadeusz Sulmowski

- remembering old Tomaszów

- Sulmowscy family. The thirties. Tadeusz Sulmowski Collection

My Roots

My dad was born in the Volhyna region. In his identity card it was written: Równe, ZSRR. He didn’t tell much about his childhood, but he always remembered Równe as an exceptionally beautiful town. He said that the Harasymowicz family came to Volhynia from Lithuania and descended from the nobility. One day dad’s grandfather Julian started to sign as Harasimowicz instead of Harasymowicz, and so it remained. Dad had a happy childhood and lived in comfort. It is reflected in his memories and photographs. Grandmother Oktawia didn’t have to work, she took care of the house. Sometimes she even had a help in the kitchen – an old woman from Ukraine. Dad mentioned that he was an illegitimate child of a Polish officer, but I don’t know the truth. The history of my grandfather remains mysterious, in the marriage certificate of my grandmother Oktawia there is a Russian man. I managed to receive the scan of his birth certificate from the Archives of Historical Records. Konstanty Iwanow was born in Warsaw, his father Eliah was a chief accountant in Nadwiślańska Railways. The family moved to Volhynia where Konstanty met my grandmother. They got married one year after the birth of my dad, I don’t know if he adopted my dad. I think Konstanty loved my grandmother very much, because he converted for her from Orthodoxy to Roman-Catholicism. Dad didn’t say anything about him, he doesn’t appear in any photographs, he is a hollow man.

- Równe. On the right Julian Harasimowicz vel Harasymowicz, grandfather of Mirosława Harasimowicz

- Równe. 1930’s. Photographs taken after the celebration of the Holy Communion of Józef Harasimowicz, father of Mirosława Harasimowicz

- Równe. On the right Oktawia Harasimowicz, grandmother of Mirosława Harasimowicz

Harasimowicz family came to Tomaszów in 1945. They wanted to keep Polish citizenship, so they had to leave Równe. Dad, his mom and her numerous siblings. He said that they were allowed to take only personal belongings, but they managed to smuggle some souvenirs, silver and photographs. They went in freight wagons, conditions were very difficult. Along the way, the train stopped in several places in Poland. According to the copy of registration book for repatriates of Staging Point in Wyrzysko, they came to this town in April 1945. They came to Tomaszów in August. The whole wagon was brought here by Stanisław Hajduk, LWP[1] soldier and brother of my mother-in-law. Why Tomaszów? Weren’t there other beautiful Polish cities? In September they appeared in the Staging Point in Łódź and they settled for good in Tomaszów. As befits repatriates they stuck together, all the siblings. At first, they lived at Berka Joselewicza street, next at 1, Bohaterów Getta Warszawskiego (Heroes of Warsaw Ghetto) street. Before the war the tenement belonged to a Jewish family. After the war the building was adopted to host several families. Mom told me that when they moved in, they found Commandments carved on the front door. On the second floor, most likely, there used to be a ball-room. A giant, decorated room was divided in two smaller apartments with dark kitchens, where another two families dwelled. Mom used to say that the house was haunted. At night you could hear strange sounds and see different things. A priest sanctified the house several times. It had to be in 1940s.

We had a neighbour living next to us – „grandma” Masalska, also from Volhynia. All these “Wołynianki” (Volhynian women) and “Zabużanki” (women coming from beyond the Bug River) enjoyed meeting together. Allegedly they visited us very often. They lived like one big family. They first met in the freight train or here, in Tomaszów. There were a lot of those from beyond the Bug River living in our tenement. We lived in the first floor, next to us Mrs. Masalaska with her daughter, opposite to her the Dworak family. Upstairs there were also the Zysiak family and the Urbaszek family, downstairs the Mąkol family – but they moved out in 1970s. Opposite to them there was an apartment of Stanisław Harasimowicz – brother of my grandma Oktawia, who lived there with his daughter Olga. His two sisters Marcelina Daszkiewicz and Wiktoria Marczewska lived just behind the wall. They all belonged to Harasimowicz family. In 1980s the house was scheduled for demolition. We were provided with the cooperative apartment.

Most wonderfully I remember my childhood and the image of our house that I loved. But not the one when they destroyed our gardens. It was a brick house, as far as I remember with the plaster always falling off the wall. There were also bricked annexes. I think that before the war it could have been a house of some rich Jew. The area around the house was quite large, our house number one was joined by the wall with number two. The square in front of the house was surrounded with a high, wooden fence. I remember that in the winter the farmers used to come with the sleighs full of products, I also remember the sound of the wheels of carriages on the cobblestone. I will never forget that, I was so sweet and amazing. There were no blocks of flats, only fields. Another houses were built at Stolarska street. The grass was so high, it was great to play there. In the middle of the courtyard there was a wooden arbor, I think from before the war. It was a place of meetings of our “older fraternity” as I would call them. The gardens reached as far as Jerozolimska street, there was no clinic there yet. Only old houses around. It was the centre of the city, but you could feel like in the country. People kept there pigs, hens, as I remember some goats and many pigeons. Many pigeon fanciers lived at Berka Joselewicza Street. I remember them calling fruuuu!!!

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Mirosława Harasimowicz

/translation/ Katarzyna Danilewicz

[1] Polish People’s Army.

- The junction of Bohaterów Getta Warszawskiego street and Jerozolimska street. 1950s. In the picture two siblings of Mirosława Harasimowicz: Bożena and Mirosław

- 1, Bohaterów Getta Warszawskiego street. Bożena Harasimowicz (sister of Mirosława Harasimowicz) by the family house. 1950s

- Family courtyard of Mirosława Harasimowicz at Bohaterów Getta Warszawskiego street

- Sura Pleszowska (born 1906), daughter of Zelig and Nachuma. She lived with her parents and siblings at 1, Bożnicza Street (today Bohaterów Getta Warszawskiego Street) until the liquidation of the ghetto in 1942. APTM no 7 Sygn. III/1778 p. 55

- Mojżesz Pleszowski (born 1913r), son of Zelig and Nachuma. He lived with his parents and siblings at 1, Bożnicza Street (today Bohaterów Getta Warszawskiego Street) until the liquidation of the ghetto in 1942. APTM no 7 Sygn. III/1859d p. 20

- Małka Pleszowska (ur. 1915r.),daughter of Zelig and Nachuma. She lived with her parents and siblings at 1, Bożnicza Street (today Bohaterów Getta Warszawskiego Street) until the liquidation of the ghetto in 1942. APTM nr 7 Sygn. III/2152 p. 6

- Itta Pleszowska (ur. 1918r.), daughter of Zelig and Nachuma. She lived with her parents and siblings at 1, Bożnicza Street (today Bohaterów Getta Warszawskiego Street) until the liquidation of the ghetto in 1942. APTM nr 7 Sygn. III/2156a p. 143

This girl

I was born in 1931, so I was eight when the war broke out. I lived on Władysławska street, near Warszawska street. I played with Jews and Germans, it was a street of all nationalities. I befriended a Jewish girl, she was more or less my age. There was a ghetto on Berka Joselewicza street, the children came out of there secretly. This girl was often visiting us, my parents. She was very dirty, my mother always told her: Remember to make sure that none of the gendarmes saw you. My mother gave her a bath, put clothes on her and fed her. There was a gendarme, called Fuchs, who shot Jews from behind. No, no, I was careful, she replied. Somehow she managed to escape them for quite a long time. One day the gendarme saw her leaving our house. She tried to confuse him by quickly walking to Warszawska street. We only heard a shot. My mother went on the street. I can’t remember her name. He killed her, that bastard. That’s how it ended with those Jews. She lived on Władysławska street. Jews lived in wooden houses, we were all friends. Poles, Germans, Jews, everybody knew each other.

The bombs

I had a lot of siblings, I was the ninth child. My father and mother came from Żyrardów. My father run a slaughterhouse in Tomaszów. In 1939, people fled to Warsaw, I couldn’t understand their mentality, under debris and bombs. At the last moment, my parents made some cold meats, they wanted to have something to ear during their travel to Warsaw. My mother walked, so did my father and my sisters. My brother passed away earlier, in the defence of Warsaw. He finished a non-commissioned officer’s school in Łódź. He was very devoted to our country and its history. Our uncle told him: Go back to Tomaszów, to your parents. Take off this uniform, but he fought and died on Three Crosses Square. The Red Cross told my mother about his death.

I was eight when my aunt Mania moved to Warsaw with her daughter Basia, who was only two weeks old. We got to the bus, because I was small and the baby was small. We drove and saw bombs. We reached Żyrardów because my father’s siblings lived there, they ran a farm. My father’s sister built a concrete bunker to hide with their neighbours. They didn’t allow us to leave, but we decided to go with my cousin to graze cows. We had no idea that the German army was there. They began to shoot randomly, one cow died. We ran away and came across a pit with calcined lime. We hid there and covered ourselves with boards. My mother and aunt screamed: The children are dead, the cow is dead!

We returned to Tomaszów, to our closed store on Władysławska street. A German woman, Mrs Lejman, lived upstairs. She looked after our house, because people stole from empty houses. We returned to Tomaszów by a cart. We came back to 21 Władysławska street. Mrs Lejman came to us and said: I am so glad that you’re here. I was looking after your house. The children used to live downstairs in one room with a kitchen. In 1945, I was 14. Russians came as soon as Germans had fled. And I had to go to school. Imagine that school was located on 4 St. Tekla street. I was admitted to that school. I used to attend secret lessons led by Mr and Mrs Dłubak on Warszawska street. I attended these lessons for quite a long time, then Mr Dłubak gave me a certificate which stated that I finished the fifth, fourth and third class. Mr and Mrs Dłuabak survived the war. The certificate allowed me to go to school on 4 St. Tekla street.

- Stanisława Czapiga, the mother of Halina Czapiga. Dating from around 1930. The photograph was taken at Aleksandrowicz’s photograph shop on Spalska street. Halina Czapiga Collection.

- Halina Czapiga. 1957. Halina Czapiga Collection.

- Halina Czapiga in 1940 or 1941. Halina Czapiga Collection

- Halina Czapiga and her sisters: Mania, Leokadia, Stanisława, Irena. Dating from around 1955. Agnieszka Misiak Collection

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Halina Czapiga

/translation/ Michalina Mieszczankowska

Feather comforters

B a r b a r a: Our mom, Stefania Pardej, had a lot of siblings, families used to be larger in the past. Our grandfather, Szczepan Pardej, ran a farm, but he was also a carter. He had a carriage and a black Landa.

C z e s ł a w a: He was not a carter, he used it to transport wood.

B a r b a r a: I remember our father telling us that grandfather was hired when President Wojciechowski arrived. They were visiting Jeleń.

C z e s ł a w a: I don’t remember that.

B a r b a r a: Because you were not always listening. Our grandfather loved horses a bit too much. He adored them. And grandfather Zaborowski was a carpenter, woodworker and one of the builders of the church in Zajączków. He was a trained worker.

C z e s ł a w a: Who was our grandfather, what did you say?

B a r b a r a: A woodworker.

C z e s ł a w a: Exactly, a woodworker, not a carpenter. There’s a difference. Our grandparents lived in Ciebłowice Duże. It was a thatched cottage.

B a r b a r a: There was a threshing-floor and wooden beds with feather comforters and large pillows. I always wondered as a kid how they slept there.

C z e s ł a w a: There was an altar in the middle.

B a r b a r a: Shelves and colourful plates inside them. A massive bench full of clothes. Our grandmother used it to store her apron and heavy woollen garment.

C z e s ł a w a: It was called a chest. It was a completely different house. There were no keys, only a hasp. These were the most beautiful years. I didn’t mind the flies, the smell of pigs or the fact that there was no toilet.

B a r b a r a: And I really liked potatoes with cream from the steamer brought out by our grandmother from the cellar.

/authors/ Barbara D. and Czesława M.

/editor/ Justyna Biernat

/translation/ Michalina Stańdo

- Szczepan Pardej and his family. 1936, Ciebłowice

- School in Białobrzegi. 1937

- Józef Pardej (during the occupation or sonn after it)

Oak wardrobe

B a r b a r a: I remember a few of mom’s stories about our neighbours. Their Easter tradition was to bring out gates if any unmarried women were at home. It was in Białobrzegi. Our dad Józef Pardej didn’t tell much.

C z e s ł a w a: Our mom used to live in a fairly desolate neighbourhood, there was only one neighbour behind the fence. The house was wooden with a front porch and wooden ornaments, built by grandfather Piotr. It’s still there and it looks the way it used to, but it belongs to someone else. No one lives there and it slowly falls into ruin.

C z e s ł a w a: There was an orchard with pears, cherries and apples. Delicious transparent apples!

B a r b a r a: The house was at the end of Białobrzegi.

C z e s ł a w a: Our grandparents’ house, formerly Polna today Wilcza, was very close to another village – Ciebłowice Duże, where our father came from. His name was Józef Pardej and he was born on 2 July 1922. Our mom Stefania, born Zaborowska on 20 July 1929, completed seven years of grade school. Our dad was in seventh grade, when our mom started the first.

B a r b a r a: They were seven years apart.

C z e s ł a w a: Dad enrolled on a sewing course in Tomaszów and graduated with a small maturity certificate.

B a r b a r a: His teacher was a famous tailor named Kujda. Mom used to tell us winter stories. There was a tiled stove in the corner of the room and we all sat next to it. There was no TV at the time, only a radio.

C z e s ł a w a: Mom was a child during the war, she was fifteen when it ended. There was a problem with forced labour. Our mother’s sister, Antonia, was three years older, but they managed to save her from forced labour. Well, she was…

B a r b a r a: The Germans wanted to send aunt Antosia and grandfather Piotr to Arbeitsamt.

C z e s ł a w a: Grandma took granddad and pushed the wardrobe away…

B a r b a r a: They pushed it together.

C z e s ł a w a: She pushed it herself!

B a r b a r a: Herself? It was a huge oak wardrobe and had to be pushed by five men. Grandma pushed the wardrobe away, squeezed our aunt in and pushed the wardrobe into place again.

C z e s ł a w a: Granddad!

B a r b a r a: What about our aunt? She hid her under the comforter!

C z e s ł a w a: But it wasn’t that easy because the Germans kept asking: “Where is he?”

B a r b a r a: Aunt Antonia turned purple, she got really sweaty under the comforter! They thought she had typhus, and they were frightened of typhus. That’s how they were saved.

/authors/ Barbara D. and Czesława M.

/editor/ Justyna Biernat

/translation/ Michalina Stańdo

- The youth from Ciebłowice. 1942

- Józef Pardej and his friends. 1944

- Tailoring Course in Łódź. 1949

Canteen

C z e s ł a w a: Mom talked about school, about Germans. They were not in danger, because there were no SS officers in their village, only the Wehrmacht. Ordinary people. They were dating girls and gave them chocolates in return for potato pancakes.

B a r b a r a: Our mother worked in a canteen at 18 Stycznia Street, today Grota-Roweckiego Street. That tenement house still stands at the corner. She told us a story about Jews who were gathered from school number 5. But we were listening with one ear and letting out with the other. I don’t remember much.

C z e s ł a w a: Our mom was petite, she was fifteen at the time.

B a r b a r a: There was one story that shook her. She saw with her own eyes how the Mołojec family were murdered. The famous Mołojec family. She went by Niwka and Kępa, and they lived near Pilica. She saw it. The second story was set during the liberation. The Ukrainians were stationed there, am I right?

C z e s ł a w a: I’m not sure. Although I remember that the route had a special name. I think it was Mongołów. It was a wild place. The officers were ok, they stationed in their rooms. The others wanted to rape our aunt or mom, I don’t know. When the officer saw it, he took him behind the barn and shot him.

B a r b a r a: They were very strict and had no qualms. She also told us a few stories about Germans.

C z e s ł a w a: But there were not a lot of Germans.

/authors/ Barbara D. and Czesława M.

/editor/ Justyna Biernat

/translation/ Michalina Stańdo

- Czesława M. with her parents. 1951

- Barbara D. with her cousins. 1961

At the sawmill

When the war started, I was eight years old and had all of my school books prepared. I have always been a bit of a bookworm, and probably always will be. Since the 1st of September I was supposed to attend the second grade of the primary school on Warszawska street, Or as we called it, “The palace”. Once it belonged to the owners of the wool factory, then it became the school no. 7 in Starzyce. Anyway, I was prepared to be a student again and there was war. Difficult times were upon us. Schools were closed down and occupied by the military. The only teaching school was a four-grade school in Komorów. My peers weren’t particularly eager to start their education, I, on the other hand, attended that school. There was only one group and four divisions. If there was only one teacher and she was giving dictation, everyone had to write it. I particularly remember one excerpt: “At the sawmill lumberjacks carve wooden boards”, or another sentence: „Our blue sierras shone serene, sublime, when ghostly shapes came crowding up the air, shadowing the landscape with some vast despair.” My notebook was full of red pen marks, but it didn’t really matter, because we were younger. Then every word had to be rewritten many times. You write “sierras” with two r’s, “boards” with an oa.

Since I was a child, my great passion has been reading. And I was attending this school in Komorów – for first years of war, till I graduated from the 4th grade. The schoolteacher, whose last name was Bun, had to teach us mathematics from the pre-war school books, because the occupiers would not print those anymore, only for the Polish language lessons the special magazine “Helm” had been issued. There were excerpts from the pre-war literature, for example from “The Peasants” by Reymont, the description of the Christmas Eve at the Boryna family’s house. I have read that so many times, that I can quote many, many passages by heart till this day. Everything printed in this “Helm” magazine must have been thoroughly censored, for the children could not learn too much about their motherland. There were poems. I had an enormous hunger for books, and so I had read them so many times that I know them by heart till today, but I do not remember any authors. There was this one poem “Sasaneczki”:

Dziś o pierwszym brzasku rannym

Niedaleko brzegu rzeczki

Zbudziły się cztery panny

Cztery młode sasaneczki.

Jedna z drugą w boczek zerka

Wokół zimno, pusto, brudno

Choć w srebrzystych są futerkach

Ale im wytrzymać trudno

(…)

/author/ Justyna Biiernat

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

based on the story of Wiesława Dębiec

Kuczer

Life was tough at that time. My brother was born In 1920, my sister In 1918. My brother and his friends were sent to Germany to become forced laborers, but it was always better to work for a rich bumpkin than at the camp. My other sister was born in 1923 and she survived somehow, as we were lucky enough to have German neighbors on both sides of our house. They were very good people. Mom was kind to them before the war, and so they helped us during the occupation – brought us bread or something else. My sister was taken away for forced labor in 1943. My younger brother, born in 1925, found a job at the train station. He would bring home some soup now and then. There was this constant fear that they would come, that they would arrest father. Despite that, dad worked at the Tomaszów’s Artificial Silk Factory, it was a joint-stock company. My dad loved horses, he used to deliver beer in barrels. Once he had worked at the sawmill, then he moved on to work at the factory. There he rode horses. To get white-collar workers, ladies and gentlemen from accounting, one would ride to Kościuszki Square and just pick them up from there. Dad had a carriage called a brake, so he could transport people to Wilanów. The director would be carried by a chauffeur in a carriage or a car. In the meantime he was also sent to get shopping, because there was this preschool for the employees’ children. We would call it the holiday village. So father would shop and transport things for those ladies form the preschool’s kitchen. He would say: “Those children are living such a good life, that they throw away cakes into the garbage,” and I would cry my eyes out. That was before the war. Dad also used to drive some people from the train station, he was a carriage driver. The name for that was kuczer, it must have been something taken from the German language. My dad would talk to people, that life was tough, that he had a lot of children. And so he got me a place in the preschool, but when I was about to go I started screaming: “I won’t go!” We had a German neighbor – an elderly person, she was very respected. Every time there was some problem mom would go to Mrs. Jesowa because she could always give good advice. And so then she looked over the fence and said: “What is all the yelling about?” and mom said that I didn’t want to go to preschool, or as we called it, the holiday village. And Mrs. Jesowa said: “Don’t make her, you might give her the terrible disease.” This terrible disease was probably called epilepsy. You get convulsions, you fall down. And so she went on: “Mrs. Albrechtowa, do not make her go, this will do no good.” And dad replied: “I begged them to take her,” because I was thin as a rake, „so she could live the good life too”.

/author/ Justyna Biiernat

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

based on the story of Wiesława Dębiec

- On the bench: Wiesława and her brother Stefan Albrecht. Wiesława Dębiec Collection

- Wiesława is the first from the right. Wiesława Dębiec Collection

Clandestine classes

Once there used to be seven grades at school, then, during the occupation, they turned into four. I know that I wrote in pencil, maybe before the war people wrote in ink. After the liberation I wrote in fountain pen. We had school desks, indentations, openings and glass inkstands with ink inside. There were italic nibs, point nibs, chiseled nibs. Teachers would pay a lot of attention to calligraphy. When we had three-line notebooks they wanted all the letters to be perfect, like in the primer. Before the war we had the Falski’s primer. All the lessons had breaks. During the break we would go out to the school pitch, we would play Boogeyman or Angular Wheel, or The Embroidered Handkerchief. I do not remember doing gymnastics. There were 30 children in my class, as far as I remember. After that we had clandestine classes. There was this teacher, her last name was Kempina. Her husband was a military man, a lieutenant. He went to war in 1939 and never came back. And she had two children. On top of that, she took care of her brother’s two kids. Her family name was Szwarcbach. Mother of those children died, and their father went to war. She was limping. We called her Kompa. Janina Kompa. She had a nice, wooden house right behind the rails, and we gathered there, in the dining room. There was no classroom, she taught us history. I went there for two years.

I remember one particularly sad incident. We sat at the table and suddenly someone ran into the house and started talking, it was some boy from the suburbs. He also wanted to join the classes. He had a notebook, a pencil and maybe some textbook. I do not remember exactly, but he seemed prepared for clandestine classes. Germans were building here railway tracks, they were transporting sand. They had these special wagons. You could fill it with sand or gravel. This boy was coming here, but, as boys do, he started climbing those wagons, and one of them tilted and squashed him. I remember her crying: “Now the Germans will find out where this child was heading,” and turning to us for help. But somehow all of this passed unnoticed.

I was studying at the clandestine classes till the liberation came. I remember perfectly Russians entering on the 17th of January. On the 18th they proclaimed liberation. I found out somewhere in February that they were opening a school. There was still war, they wanted to take over Berlin. It’s February, and they brought school desks to Kolejowa street. There was the school no. 5, and there were rumors that we would have classes there. We ran to see. I remember this moment, I will never forget it. Some cars drove up to the street, and they took out the school desks. It was such a joy, such a joy that we can finally learn!

/author/ Justyna Biernat

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

based on the story of Wiesława Dębiec

All days’ work

My name is Antoni Sipiński, my birth date is fifth of September, 1929. In 1945, around 20th of January, when Russians stepped in, I went to be an apprentice in Komorniki next to Wolbórz. I was a very good student at school, I had school reports with distinction. Once you grew up you had to work. I could go to school, Wolbórz had a semester junior high school. But they had to teach a one-year-program for two years, because there were no teachers. So my father got me the apprenticeship. “Because who has the money to buy you clothes?” He said. In 1948 in Piotrków I became a journeyman, and obtained a master craftsman’s certificate in Łódź, once I went back from the army. You had to start from basics, you did what the foreman told you to do. You worked all day, from seven in the morning to seven in the evening, and all nights during holidays. When a man wanted to sleep, he would just do it wherever. After such a short nap you could go home only on a Sunday morning. That’s how much work we had to do. Sewing started from small steps. The foreman cut the material, and each one of us would get his own piece – for trousers or a jacket – and start working. There were eight boys. My foreman’s name was Julian Lisma. He had been the apprentice of Ludwik Mączyński in Tomaszów.

I had been living in Komorniki during the whole occupation. I had to work on the farm, because my father, born in 1902, had been held captive by the Germans, and got back home only when the war ended. At the last moment Poland called all man to war. So he spent five years in Germany, and I was the man of the house at that time. We had a horse, and I had to go work at wagons, at so called “podwody”. Germans took all the men they needed. In Bogusławice, where there is the manor, they were building an airport, so they would bring wood from Drzewocin. There are stallions in Bogusławice. The SS, those Germans who wore a cadaverous head in the eagle emblem, they loved those stallions. The oat for the horses was transported in wagons from somewhere to Baby, so a German man would take a whole row of our wagons and we would go to Baby to fetch the oat for the stallions.

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Antoni Sipiński

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

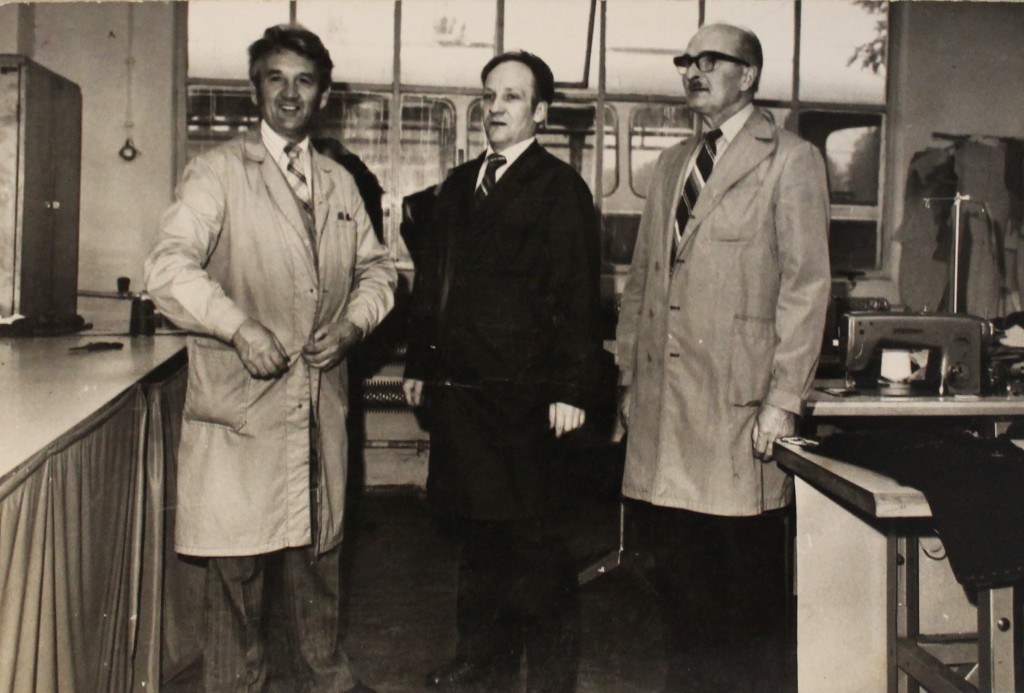

Tailors. Antoni Sipiński Collection

Scissors, the measuring tape, the ruler

A journeyman could sew, but not cut. He could work at his own workshop, but he couldn’t have apprentices. If I wanted to have students, I had to obtain a master craftsman’s certificate to be able to teach. I remember my journeyman exam; that was in Piotrków. The foreman cut the fabric, and I took the given piece to the examination board. Then the chairman of the board said: ”Sir, why don’t I give you a piece to tailor, would you do that one instead of yours?” I replied: “Of course! I will leave my tailor’s bag here, you will cut the sample, and I shall sew anything you need.” So he says: ”We have got here supervisors of the Piotrków’s guild, so I would like it to be done perfectly, so you can take the job.” I said: “Absolutely!” And I was sewing for a few days at the craftsman’s workshop. I took the first part of measurements, and he placed an order. It came, and we tried it on to assess how to tailor properly. When the second part of measurements was done, he placed an order again. It came. The second order contained sleeves and a collar, the first order contained only the front and the back.

When I started my apprenticeship we had no electric lighting. Wolbórz got that installed only in 1947. The youngest apprentice would have to take the bag and go downstairs to the baker. You had to collect the coal downstairs. Then there were these iron chimneys, and you had to light a fire in two or three of them.

What does a tailor need? Scissors, a measuring tape, a ruler for drawing, a pencil and an iron. And a sewing machine of course. Mine is and old Singer, a real grandma. I also got a new multifunctional machine, and it finishes the overedging really fast, but in the old days we had to do that manually, so the trousers wouldn’t fray. The stitching also had to be done by the tailor himself. Now the machine does it in no time. You set the sewing machine for the right stitch and it just sews in a straight line.

Before you started sewing trousers, you had to iron it. Front trouser legs were nothing, comparing them to the back trouser legs. Oh, to iron them properly under the knee! It was so difficult to do the back leg well! Or the back of the jacket. To iron the shoulders so that they would be adhesive. The sleeve of an outer shell of a puff had to be sewed in and tacked.

Once foreparts were always made on a canvas, and there was a haircloth, now there is no haircloth, nothing. You turned clothes inside out, if someone damaged it and it was all split or frayed, but still fit for further use. So you sewed it once again, turned inside out. In the old days there was no fabric glue, everything was natural.

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Antoni Sipiński

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

- The journeyman diploma of Antoni Sipiński

- The foreman diploma of Antoni Sipiński

Furriery

My uncle taught my father tailoring. He was a brother of my father’s grandmother, his name was Szubert, as I recall. He had had a tailor’s workshop on St. Anthony street. Later he moved to Łódź, and so did my father, so he could work there as a tailor. I was born in 1960, and he moved back to Tomaszów In 1963, maybe 1964. All that time he had been working, sewing jackets, light overcoats. From my mother’s side it was my grandmother who was a tailor. She had this nice sewing machine with a handle, and there was no bobbin case, it was a lockstitch sewing machine.

I went to the vocational school, they taught me everything from the basics – how to sew pockets, how to make piping, how to sew a zipper. Small steps, only later did we start making trousers or vests. Now there are no requirements to have your own workshop in order to become a journeyman or a master craftsman. The technical school’s diploma is an equivalent of a master craftsman’s certificate.

I had graduated the vocational school, and then went to the secondary technical school of clothing, and I worked in Pilica till 1981, I think. My training took place in a pattern showroom in Pilica with mr Antoś – I was sewing vests. I knew how to make trousers, vests. What to do? I was too young to be a master workman, I had no job seniority. I was interested in furriery, and my sister happened to be a tailor and a furrier. She did her training on Żwirki and Wigury street, she had been working for a furrier who later moved to Piotrków. So I went there too to learn how to sew furs and sheepskin coats.

I took up furriery, but the art of furriery is now gone. I learned how to be a furrier in Piotrków. There we sewed sheepskin coats, furs, caps. All of this is gone now. Once people would keep nutrias, there were a lot of nutria furs, now it went out of fashion. Next to Pilica river there was a fox farm. Then ecology came, killing animals became unethical, so they stopped. The fashion changed, and winters became warmer. In our times, the first of November would become a fashion show – suits, sheepskin coats, furs, overcoats. Today November is so warm you can go outside in a jacket.

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Sławomir Pawlik

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

- Overlock. Sławomir Pawlik Collection

- Iron (used with carbon). Sławomir Pawlik Collection

- Sewing machine (Singer). Sławomir Pawlik Collection

- Prasulec [using for iron sleeves]. Sławomir Pawlik Collection

The pattern room

The atmosphere in “Pilica”, the pattern showroom, was very nice, it was friendly. There were no problems. No one would go behind a colleague’s back. I’ve got some good memories, but it is such a shame that the workshops are gone now. They were hiring a lot of women from Tomaszów and nearby villages. When I went to school there I really liked it. There was a beautiful porter’s lodge, mannequins were standing, behind the glass, illuminated. Garment sewing factories were wonderful, they had transported machines from Italy, and you would put the jacket on a mannequin and iron it from the top and from the back. A very modern technology. We would sew uniforms, railway ones as well, We even had orders for corduroy suits which were later shipped to an American company. Corduroy was in fashion back then. The only worthy competition for “Pilica” was Bytom.

There was this plastic artist, she would pick the right colors, to match the lining with the outer fabric, for example. We had the pattern room, the cutting room, a production briefing room; templates, grading. In every department there were lots of employees, the whole teams. In one team they were sewing only trousers, in other only jackets.

Each team had a master workman. We were hiring ironers and quality inspectors. The final touches were done by women, they had to see the product on the mannequin, cut off the unnecessary strands. All had to be perfect, if not, it went back for adjustments. We had quality check done on trousers, vests, on everything. Each piece of clothing had to be examined, otherwise it couldn’t be transported to the warehouses.

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Sławomir Pawlik

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

The tailor was an artist

S ł a w o m i r: The tailor was a true artist. Once he was a treated like a half prince. He had reputation, he had respect. All families would go to see first and second fittings. At the tailor’s workshop you could try on clothes, but you could also chat. In the old days we had no templates, you would put the fabric on the table and draw a construction grid. All of it came straight from your head; you had the sizes, so you drew and cut accordingly.

A n t o n i: All had to be done step by step, in accordance with client’s wishes. The time before holidays was always busy. I remember one client who wanted shorter sleeves. I must have been really sleepy, I closed my eyes and cut through a sleeve with my scissors. Only when someone shouted “What are you doing! What are you doing!” „My goodness!” did I realize what had happened. And what to do now? We had to remake this sleeve, sew it from a new fabric. Once I also cut through the chest, till the armpit. I did it because of my huge exertion.

S ł a w o m i r: By chest he means the chest pocket, the buttonhole, in turn – is a loop made in the chest. The whole lapel was called “bezet”.

A n t o n i: I have been maintaining the list of Tomaszów’s tailors for thirty years. I started when I was working in “Pilica” and I keep writing it till this day. We all knew each other. We all paid the lump sum, taxes. The due date was always on one single day. So we would bump into each other when we went to the presidium to pay. There was this restaurant nearby, we would all go there, grab a drink, have a nice, long chat.

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Sławomir Pawlik

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

“Pilica”. Antoni Sipiński – first from the left. Antoni Sipiński Collection

Our generation will perish

I was born in 1932. I’m from Sangrodz.

We used to go dancing, we used to fight too. We would beat the heck out of each other. But there were never any casualties. There were a few firehouses – in Komorów, in Łazisko. We used to go there. There was also one in Ujazd, but we never got there; we didn’t like boys from Ujazd.

When I was young I had to work at a farm. Everything had to be done by us. I had five brothers and two sisters. People were a bit afraid of my family, the boys were so valiant and militant that others feared them. No one dared to beat me up cause they would get bashed. Mom died right after the war had started. I attended both school and the apprenticeship.

I got all the journeyman and master’s certificates. I gained my master’s certificates in Wrocław. I went there for the exams and to attend special courses. I know Wrocław very well, I served in the army there. I almost stayed there for good, I even became a sergeant in the armored division. It was the 50s. During my service I was rolling in money. I joined the army when I was nineteen, and I had learnt everything about tailoring by then. I was the only tailor in the unit who knew how to make a uniform. Other needle workers who served with me couldn’t do it. They could maybe sew together a pair of pants, but not a uniform. My plan was to stay in the army, but I had an accident. They kept me in traction for nine months. I had my left leg broken, some driver ran me over on Zawadzka street. Maybe that’s why I wasn’t so eager to go back to the army; besides, I’ve noticed this specific discrepancy in the military. I didn’t like it at all – a lot of slackers from the party and troopers. But if I chose to go back I would have had one fine military career; I was very athletic. I was a great runner and a great swimmer. Swimming was particularly important in the armored division, cause what else can you do when the tank gets stuck in the water? Nothing but drown.

I liked tailoring – that’s why I stayed in this business. There was this will, ambition. It used to be more common for a man to be a tailor. There were no factories. My favorite moment is when I’m done and I see that I have sewn exactly what I wanted. That it is chic and decently-made. Once the design wasn’t as perfect as it is today, but the production was made on canvas. You designed the cut on canvas, and trimmed the front so it would fit this design. Today clothes are glued together. Our generation will perish, there will be no more tailors. The best tailor is also a designer.

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Zygmunt Debiec

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

The wadded jacket

There was a tailor’s workshop on Krzyżowa street. They made protective clothing and workwear, and during the winter they made so called padded wadded jackets. They were worn as regular jackets. Fornalska was the main producer. I was just starting my work there. I worked in services, but it was all one company, so we were under Fornalska’s supervision – tailors and those ladies who sewed, because it was mostly the ladies who sewed the workwear. Both for the winter and the summer. The process of production was pretty long there. It was very warm clothing – denim on top, under it there was cotton and the lining.

We had a foreman and a master. The foreman helped the ladies with the production process, and the master did all the management. One or two masters supervised the production, recorded the whole process. It was good for us that “Pilica” emerged later. There we made garments for men, we sewed suits, mainly for the Soviet Union. Later “Pilica” started making clothes for the Western market. Clothing industry is quite well developed in Tomaszów.

You had to make what they told you to make. Draw the pattern and make the clothes. The worst and most difficult were sheepskin coats. No one wears sheepskin coats today, winters are completely different now. But then winters used to be harsh, so everyone wore it. Today you can wear simply put on the wadded jacket.

I learned fast, a lot of servicemen would come to us when I was working for Fornalska. My master’s name was Adam Wojdyło, he was from Tomaszów. He taught me and examined me for a journeyman.

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Zygmunt Debiec

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

Zygmunt Dębiec Collection. In the picture he himself

The pattern room

I worked at a pattern room. At the pattern room employees worked on patterns. There was a drawing and we had to copy that drawing and make the pattern. Most of the workers were men, there were some women after technical secondary school. They usually worked in the production area as forewomen. You could also see men working as masters. There was this woman, a graphic artist, she was assigned to our pattern room, and she also worked with administration. Patterns and designs were outlined by the tailors. We had a few sewing machines, four or five. We produced the design there first. The master would draw, make a template, and the rest of the tailors would make the pattern. Then a model from Łódź would come and wear it for us as a presentation. Master tailors were looking carefully if something had to be removed or not. Sometimes they rejected the pattern altogether. If the commission didn’t like it, the template was declined as well, and we couldn’t start its production. The commission was composed of local master tailors and one specialist who came from elsewhere. Everything had to be perfect – measurements of the jacket, the length of the sleeve, the collar, all had to fit. They could come closer for a more detailed observation. The model had to parade like this a few times – to show the front, the back, sides. Master tailors at my pattern room were: Krajewski, Porczyk, Sipiński. My master, Wojdyło, was the head of it all.

There were no conflicts. There were some failures during the production, but it was for the master to decide whether those employees should be paid full salary or not. At the pattern room the attention to detail was really important. Sometimes we would go to fashion shows in Wrocław, Łódź, Kraków. Everything had to be made perfectly. My designs required tons of hard work and travelling.

/author/ Justyna Biernat

based on the story of Zygmunt Debiec

/translation/ Małgorzata Lasota

aunt Helena Długołęcka and grandpa in Gostyń. Magdalena Abraham-Diefenbach Collection

DISPLACEMENT

In December 1939, grandfather Inek together with his sister Stachna, mother Helena and one-year-old stepsister Małgosia, were displaced from Gostyń with the first transport to GG. At that time there were no transit camps in Poznań or Łódź. First, they were deported to the Oratorian Catholic Boarding School on the Holy Mountain in Gostyń, where they spent three nights. The displaced people included community workers, members of the Polish Western Association and their families, wives of executed prisoners, teachers, wealthy craftsmen, wealthy peasants, and merchants. They had to empty their apartments for the Germans. Each of them could take up to 20 kg of personal items.

On December 4, 1939, they were led from the Holy Mountain to the station in Gostyń and by passenger train to Rogów (on the route from Łódź –Warsaw, just outside Koluszki), where they were taken to a narrow gauge railway, to open flat wagons heading in the direction of Biała Rawska. They got off at Rawa Mazowiecka station. The whole group spent a cold December night on straw in a bombarded brewery.

In the morning small carriages with one or two horses started to arrive. The carriages were filled with peasants in sheepskin coats. The district divided the displaced people into individual villages, some of them went to peasants, and Grandfather with his family went to the manor house in Byliny Stare, Boguszyce Municipality.

They were given one room in which they spent the whole winter. The manor house belonged to the Zaorski family, nice people who owned fish ponds. Grandfather ate a lot of fish back then. The displaced ate dinners in the manor outbuilding, but on Christmas Eve everyone ate together in the manor house.

Support for the displaced was provided by the Central Welfare Council. Everyone had to cope somehow, the locals fed them and provided them with support.

Aunts Anna Kordzińska and Lucyna Cwojdzińska together with her husband Ignacy were displaced from Leszno to Tomaszów Mazowiecki in the winter of 1940. Someone wrote to the aunts when they were still in Leszno, that’s how they got the address of grandfather in GG.

Józef Kordziński in 1945. Magdalena Abraham-Diefenbach Collection

JOB

In the spring of 1940, Grandfather found a job in coal and wood warehouses belonging to Wilhelm Wegga (Kohle- und Holzversorgung) in Tomaszów Mazowiecki. At that time, he lived with his aunt Cwojdzińska at Sosnowa Street, and later at Szczęśliwa Street. He worked there for about 1.5 years.

Wilhelm Wegga was a volksdeutscher and he cooperated with the Home Army.

Helena’s mother worked as a teacher at a school in Ossowice, Rawa Mazowiecka district, from the spring of 1940.

Grandpa changed his job and worked in German car workshops and a transport company in Tomaszów Mazowiecki. He lived on the premises of these plants, in a barrack, together with two Jews, one of whom was an intellectual from Łódź, he knew “Pan Tadeusz” by heart. The owner of the plants was Gerhard Denkhaus from Duisburg. Grandpa trained to become a car mechanic, he got his driver’s license. The plant employed a few Jews: welder Reichmann with a boy, mechanical engineer Goldstaub. A Jew with Polish name – Sikorski – was the only survivor.

The plant area was covered with matzevas from the Jewish cemetery.

FRONT

In 1944, during the Warsaw Uprising, when the Russians were on the Vistula line, Denkhaus’ German plant was to be evacuated to Duisburg and Grandpa was supposed to go with them. So he took his bicycle and ran away to Rawa. Grandpa rode his bike from Tomaszów to Rawa, and the Germans were running in the opposite direction. No one asked him any questions.

Krokowa 2006

Memories of grandfather Józef Kordziński were written down by

Magdalena Abraham-Diefenbach

Translation: Michalina Stańdo

Lucyna and Anna Kordzińska. Magdalena Abraham-Diefenbach Collection

Compote

I

It’s September 1939. Polish prisoners of war detained by the Germans are stationed in Tomaszów Mazowiecki. Among them is a reserve second lieutenant Zenon Szczech. He takes care of the sick and wounded, he was awarded the title of doctoris medicinae universae. With the consent of the German authorities, together with two other doctors, he is staying in Tomaszów for a while. He will run the Infectious Diseases Ward of the Municipal Hospital. The building surrounded by a high fence will become a safe shelter not only for the sick. It will also house those who are in danger of being arrested or taken away. Doctor Szczech will welcome them, make false diagnoses, and extend their hospital stay if they need more time. After all, the Germans would not cross the gates of a property guarded by the sign “Achtung – Seuchengefahr!” Soon Tomaszów will welcome Elżbieta. She is nineteen and she has just given birth to her daughter Krystyna. As the wife of a doctor and lecturer at various Łódź institutions, she will be displaced from their apartment, which will be taken by polizeipräsident Invoking the Geneva Convention protecting prisoners of war will be of no help. In Tomaszów, they will live on the main artery of the town. They will receive two rooms from a Jewish family – Hersz and Ajdla Rubinek. Soon, doctor Alfred Augspach, director of the Municipal Hospital, will move into the tenement house. None of them suspects that they will spend the entire occupation in that tenement house.

II

Little Krysia loves to jump on the couch. Hersz Rubinek allows her to do that, he’s almost like a grandfather to her. His children are grown-up, Ruwejn is twenty-one, Hinda is seventeen. Hersz is a merchant involved in the life of the Tomaszów community. A few years ago, together with a rabbi and well-known factory owners, he became a co-founder of the Jewish Schools Society. He hangs around with the Thomaszów intelligentsia. They share the apartment in friendship, Hersz jokes that Krysia has a Jewish “kepełe” (head). Doctor Szczech is released from captivity and starts working in the Social Insurance Office. He has a pass, he can even go to his patients for home visits during curfew hours. He moves around in a one-horse carriage, or by bicycle – for longer trips. He is working really hard and he will soon appear in the newly created ghetto with medical assistance. The Rubinek family will also have to move to the ghetto located near their apartment. Sometimes they will return to their neighbours for food. Teenage Hinda Rubinkówna will get involved in the activity of the “Akiba” youth movement. A group of teenagers of Aryan beauty will gather in the ghetto, speaking fluent Polish without any traces of a Yiddish accent. Their motto will be: resistance and disobedience through active work and mutual support. No submission or passivity. Hinda will become a messenger of the Jewish Combat Organization, she will travel to the Krakow Ghetto and carry out sabotage actions. She will die in 1943, a year after her parents and brother in Tomaszów or Treblinka. At that time, doctor Szczech will be placed under Gestapo arrest for the alleged unsatisfactory treatment of a German man. He will come back abused and broken down.

III

The two-storey Augspach villa is located in the town centre. Doctor Augspach has been running the Municipal Hospital for twenty years, he started with no electricity or telephone. He made sure that a chemical laboratory was built in the hospital and more doctors and feldshers were employed. He has a daughter named Felicja, affectionately called Litka, and a son named Aleksander. His wife Marta is from Tomaszów. He also comes from Tomaszów, although his parents came from Grünberg in the 19th century. He is the only doctor in the town, he helps civilians and wounded soldiers of the Polish Army after the first bombings of the town. He has just taken in three doctors- prisoners of war. They are under his care, he lets them stay in the rooms upstairs. Doctor Augspach signs an official declaration and undertakes to perform his duties according to the German administration. Despite that, he creates a field hospital and supports his son, who is active in underground organizations, in the Service for Poland’s Victory and the Union for Armed Struggle. Aleksander will become a soldier of the unit of major Henryk Dobrzański. Doctor Augspach, doctor Szczech, doctor Jaskiewicz and medical student Tadeusz Bazylewicz, “Tadek”, will get involved in helping the wounded Hubal’s soldiers. Antoni Sokorski, an employee of the hospital, will deliver bandages and uniforms left by the Polish soldiers fighting in the September Campaign. Pharmacists from Święta Tekla, Antoni Butkiewicz and Julian Ambroziewicz, will also provide their support. Meanwhile, the Augspachs have to leave their villa, which will soon be occupied by kreishauptmann. They become neighbours of the Szczech and Rubinek families. Little Krysia befriends twenty-year-old Litka. She also meets Borusia, daughter of Woldemar Gastpary, vicar of the Evangelical-Augsburg Church located on the opposite side of the road. Together, they play with her beautiful dolls. Gastpary is in detention in Piotrków Trybunalski, and he will be soon sent to the Dachau concentration camp. The parish priest, Pastor Leon May, will suffer a similar fate and will preach anti-Hitler sermons.

IV

Augspach, just like Szczech, crosses the gates of the Tomaszów ghetto. After all, he knows Doctor Efroim Mortkowicz, who now runs the ghetto hospital. He apologizes to his old colleagues for not visiting them. Mortkowicz has recently arrived in his hometown of Tomaszów. He returned from nearby Łódź after the outbreak of war. He worked there as a surgeon. He stays in the ghetto with his little daughter Krisza, his twin brother Menasze and his nineteen-year-old daughter Raca. He is a member of the Jewish Community Council. Soon the ghetto will be liquidated and on the Purim Day they will be transported to the Jewish cemetery by truck. The dug graves will be waiting. The Jewish district will become more and more deserted. Warsaw insurgents will arrive in Tomaszów. Doctor Szczech will give shelter to some of them. Krysia will have a little brother. Soon, the war will come to an end, Krysia will meet Litka’s husband, Oskar Lange. She will move with her family to Łódź, her parents’ hometown. Doctor Szczech will be taken to the Polish Army as a captain. He will return from his unit seriously ill and he will never regain consciousness. Meanwhile, the Soviet Army enters Tomaszów. There’s an alarm, everyone needs to go down to the basement. Doctor Szczech takes the children, they have just finished their dinner. Little Krysia burst into tears, looking at her compote with longing eyes. She loves this ruby red dessert, which she will no longer be allowed to drink and whose taste will stay with her for many years.

Annex

The above text is based on a conversation between Justyna Biernat and Mrs. Krystyna in 2019 /translation Michalina Stańdo/, as well as on archival materials and scientific studies. The attached photographs come from Mrs. Krystyna’s family collection, and their descriptions are quoted from the conversation.

Photograph I

“Mom was born in 1920. She was nineteen years old when she was displaced. My father was fifteen years older than her. Mom used to say that he played volleyball and cycled so well that he was like her peer.”

Photograph II

“It was a nice apartment with a balcony. I remember the Rubinek family, they were so nice. I remember the couch he let me jump on. It was a couch with a shelf and soft pillows. He watched over me while I was jumping. My mother wouldn’t let me walk on the armchairs at home. He was a bit like a grandpa to me.”

Photograph III

“Mom always said Mrs. Augspach, because she was a lady who kept her distance. She was very elegant and she took great care of herself. Augspach was a great patriot, although he was of German origin. My father lived with the Augspachs. Augspach gave shelter to two or three doctors and he kept them in his house. He vouched for them with his head.”

Photograph IV

“This is the hospital where my father ran the Infectious Diseases Ward. My father also had a private practice, but didn’t take any money, because there wasn’t any to give. The patients brought chickens or eggs, so there was always some food at our house. It was a conglomerate, we lived with the Poles, the Rubineks and an Austrian officer. Mom said that he knew that we were feeding the Jews but he didn’t say anything.”

Photos from Mrs. Krystyna’s Collection

Photos from the collections of the State Archive in Piotrków Trybunalski (Branch in Tomaszów)

- Doctor Alfred Wilhelm Augspach (1879-1955)

- Pastor Leon Witold May (1874-1940)

- Pastor Adolf Woldemar Gastpary (1908-1984)

- Doctor Efroim Mortkowicz (1892-1943)

- Hersz Rubinek (1888-1942)

- Hersz Rubinek (1888-1942)

Bądź pierwszym który skomentuje