NEWS

We are very happy and proud to announce that Justyna Biernat received an honourable mention during the 2020 POLIN Award ceremony.

Finał konkursu Nagroda POLIN 2020 | Muzeum POLIN – YouTube

Justyna Biernat a nominee in the 2020 POLIN Award

Photo: Maciek Jaźwiecki. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews grants the Award to individuals or organizations engaged in preservation of the memory of the Polish Jews. This year, one of the nominee is Justyna Biernat, PhD. We are very happy and proud that Justyna Biernat’s work and Tomaszów Mazowiecki are visible and aprreciated.

https://www.polin.pl/en/nagroda

Tomaszów Mazowiecki Ghetto: A Guidebook

We are very happy to inform you that dr Justyna Biernat has received a grant funded by the Forum for Dialogue Foundation for writing and publishing Tomaszów Mazowiecki Ghetto: A guidebook. The guidebook will consist of the map of the ghetto, description of the history of the ghetto, photographs and excerpts from the testimonies. Dr Biernat will also give a paper on the history of the ghetto of Tomaszów and she will take participants for an educational walk in the footsteps of the ghetto. The guidebook will be released this year and available for free. It will be published in Polish and English by the Spaces of Memory Foundation.

Ms. Mira Ryczke Kimmelman

With a heavy heart, we inform you that on April 17, 2019 Ms. Mira Ryczke Kimmelman passed away. Ms. Mira was one of the characters of the letters from the ghetto in Tomaszów Mazowiecki, written by Lutek Orenbach. She was born in 1923 in Sopot, in 1940-1943 she was living with her family in Tomaszów. After the war she moved to America and was very active in her community in Oak Ridge.

Thank you so much, Ms. Mira, for our conversation over the phone. We promise to remember and remain your story.

Read more about Ms. Mira here.

Ms. Mira (source: Oak Ridge Today)

Letters from the Tomaszów Ghetto – Publication

The Spaces of Memory Foundation kindly asks you for donation for the publication and critical edition of the letters from Tomaszów Mazowiecki ghetto. Here you may support the project and below you may find the project description:

https://pomagam.pl/en/listyzgetta

Letters from the Tomaszów Ghetto is a project focused around the publication and textual criticism of letters written by a 19-year-old Izrael Aljuche Orenbach to his girlfriend, Edith Blau. Izrael, also called Lutek, had been writing letters and sending them from Tomaszów Mazowiecki to Miden continuously since 1939 to 1942. He wrote in Polish. Edith, In turn, wrote back In German. Lutek met her and fell In love with her In Bydgoszcz during the 30s.

In his letters Lutek describes the life in the ghetto and focuses on his artistic life, very active back then. He and his friends from the ghetto establishes a theatre and an artists’ club.

“Sometimes there is this moment, when thoughts float from you straight towards poetry and back, and when this music plays inside me, or when something reminds me about the theater (theater, oh, the theater!) and I start playing a part in front of myself. Once we had this nice atmosphere. We gathered at my friend’s apartment one evening (…) Fredek played sentimental tangos. The room was completely dark, a couple of people were dancing. Black figures glided slowly in front of windows, and all of that created a tremendously sad image. The whole tragedy of the Jewish youth was depicted on those silhouettes. Will we ever get to be really happy? Or will we carry the stigma of war forever, this deep sorrow, which comes out only during certain moments, during certain moods. We all mask ourselves really well.”

[The letter from 3rd of September, 1940]

“You should know that our „theater” is a real sensation in Tomaszów. People are thrilled. The latest show will be now played for the fifth time! Bella, Fredek and I are the most popular trio in town. Everybody says I should become an actor. You should know that we have got a lot of intelligentsia folks and artists (most of them are from Łódź), so those compliments, coming from them, are quite pleasant to hear.”

[The letter from 4th of March, 1941]

The book titled Sen o teatrze. Listy z tomaszowskiego getta (The theater: a dream. Letters from the Tomaszów Ghetto) will feature all of the preserved letters (almost a hundred of them) and sketches drawn by Lutek Orenbach ( 17 caricatures, 1 auto-caricature, and the drawing on the cover of the notebook), as well as an extensive introduction depicting the ghetto in Tomaszów, illustrated with archival photographs. The book will be prepared by dr Justyna Biernat. She received a permission for publication and textual criticism from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The correspondence, which now can be found in the Museum, belongs to the collection of Edith Brandon, the addressee of the letters. The book will be published in Polish.

The Spaces of Memory Foundation received a grant won during the grant competition organized by the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland. The grant will cover the part of the publication’s costs.

The Foundation asks for the financial support for the publication and thanks all of the donors for contributing to the common protection of the multicultural heritage of Tomaszów Mazowiecki.

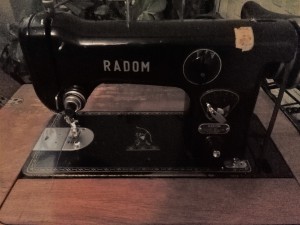

Tailors Exhibition

Spaces of Memory Foundation has been already working on its first exhibition relating to tailors from Tomaszów. The Foundation has been doing research in the archives, meeting tailors in order to collect their stories as well as their old pictures. The Foundation would like to thank to all the tailors who have shared their memoirs, special thanks to the family of Jerzy Kula. The family decided to donate the sewing machine to the Foundation.

We would be delighted if You wolud like to share your story. Please, contact us: fundacja.pasazepamieci@gmail.com

Habemus doctricem

We are so happy to announce that yesterday 8th November, 2017 Justyna Biernat, the President of the Spaces of Memory Foundation, had the public defence of her doctoral thesis: “Dramaturgy of Lament. Mourning and Ancient Greek Tragedy in the circle of Psychoanalysis”. The Ph.D degree was awarded to her at the Jagiellonian University, Theatre and Drama Studies. She graduated summa cum laude. Congratulations!

Writing Competition

The Spaces of Memory Foundation invites you to have a read of the best texts written for our Writing Competition “The Carriage of Tomaszów” inspired by the pre-war pictures of carriages in Tomaszów. The competition was a part of our “Membrany” project. It has been co-financed by the Museum of Polish History in Warsaw within the framework of the “Patriotism of Tomorrow” programme. The jury of the Writing Competition: dr Karolina Wawer (Jagiellonian University), Piotr Gajda (Migotania and Arterie Journals) Bartłomiej Sęk (The Spaces of Memory Foundation).

Piotr Kwaśniewski

The carriage drive

The carriage was trailing sluggishly through St. Anthony street, now lit with street lamps. There was a passenger sitting in the leather box, a man appearing to be in his prime, dressed in a dark, two-buttoned blazer and a silk tie. On the free seat next to him was laying a black umbrella with a wooden handle, and on his knees – a thoroughly folded, latest issue of “The Echo of Masovia”, for an unknown reason indispensable to the man at such a late hour. Horses’ hooves were thumping on the wet from the rain cobblestones. The passenger, listening to this steady beat, set his sight on the broad shoulders of the carriage driver, clothed in a graphite coat. It had come to his realization that ever since he met him, ten years ago, he had never seen his face. He would see him only in the evenings – and only from the back. Every time he would get into the carriage, it was only through horses’ coloration and the unique shape of the vehicle that he knew there would be this particular man in the box seat. The voice would later complete the image. All of a sudden a peculiar thought crossed his mind: d i d t h e c a r r i a g e m a n h a v e f a c e a t a l l? This reflection was immediately deemed by him as idiotic.

– You were right – said the passenger, trying to appear calm.

His only answer was the rustle of rain banging on the roof and the familiar thumping of hobbled hooves. The man pretended to be indifferent to this rude silence through the whole length of the street, watching shop windows, now sunk in the darkness. When the vehicle reached Tkacka street, and he was still left with no response, his patience ran out.

– For God’s sake, you were right! – exclaimed the passenger with an upset voice – Two days ago we were supposed to go to the Budy Neufeld show: I excused myself, saying I was feeling ill. And so she went alone. I immediately had a new key set made, requesting an absolute discretion. The rascal was smirking cunningly and made me pay a fortune – but he did what I asked him for, and, as far as I know, he didn’t say a word to anyone. Money can make any lips sealed – but never mind that. I searched through her mail and I found that thing you have mentioned. How I wish I had never read that! Jesus Christ, the things he wrote to her! Such lewdness, obscenity! – the passenger was getting more and more emotional – Letters and notes, piles of them, loads of them! Most do not have dates, but the number alone speaks volumes of how long ago it must have started. And after all I’ve done for her! I married her because of my kindness, with no views to any profits. For me it was almost a misalliance! Her family was swamped with debts, they owed a fortune to the old Bornestein. The interest was eating them alive! So I lent them a helping hand! If it weren’t for me, her mother and father would have had to work hard for that money, standing twelve hours a day by the looms, in the factory! And this is my reward: shame and injustice! Dear God…! – the man got silent, overwhelmed with anger and sorrow.

For a few brief moments the only sound accompanying both men was the monotonous music of the carriage, trailing in the rain. When the vehicle passed Dawid Bornstein’s estate, located at Warszawska street, the passenger, now calmer, asked:

– How did you know?

And one more time, the carriage driver remained silent.

– Anyhow, how stupid of me to ask! I suppose everyone knows by now. I think it’s a God’s law that the husband is always the last to find out!

The passenger laughed nervously, with his face turning red in the dark.

– A few people are making assumptions. I am the only one who knows for certain. Me and you – the cold, indifferent voice of the carriage driver rang in the man’s ears for the very first time this evening, and made him shiver. The passenger was continuously amazed that although the driver seemed to be talking very quietly, he could always understand him perfectly – and vice versa.

– So how did you know ? – the man went on – I am not even asking about this incident. I am asking about everything. Everything you have uncovered. That the maid was stealing. That the Zwierzyński’s brother wanted to outwit me. And later, about that intrigue at the magistrate. And the last thing, the worst of them all: this.

The carriage turned left into Kołłątaj street, while the passenger continued his trace of thought:

– You know things you’ve got no right to know about. And you are never wrong. As if that weren’t enough, you always know every solution to my problems. And I, for some reason, keep listening to you: and the issues are getting more and more acute. What is more, as God is my witness, so far I’ve been only benefitting from that. Your advice is invaluable, I play my opponents like children. And I assure you, I shall never make you put my gratefulness in doubt. But now I want; I have to know: h o w ?

Silence. Even the rain seemed to have stopped banging on the roof, and the sound of the hooves appeared to have been coming from the distance.

– You’ve driven them, haven’t you? It’s the only way. Are they really blatant enough to drive around Tomaszów in carriages when I’m not looking? Or perhaps you were just taking him home, that pig, dead drunk after some libation, and he spilled everything. Yes, that must be it.

The carriage driver kept his silence. There were fewer and fewer streetlamps lit on the streets. There, in the dark, the confused passenger, focused on his thoughts, had trouble recognizing their current location. He wasn’t worried though: for he didn’t have any specific destination to reach. The reason of his ride was to talk to the carriage driver.

– So that’s how you obtain all the information. You drive people. You keep your silence, but also keep listening. Your hearing is excellent, as well as your memory. Folks think that you’re just doing your job, without paying any attention. So they talk. To each other, or directly to you, when drunk. They talk too much. And you just listen.

– If so, then why haven’t I seen you before. Gathering knowledge takes time. You seem to be new around here. You’ve moved from Łódź, haven’t you? Or perhaps I’m wrong?

Silence, combined with the darkness.

– Why is it me that you’re helping? – asked the passenger.

– W h y i s i t y o u?! – there was mockery in the usually indifferent voice of the carriage driver – What makes you think that you are somehow exceptional? Do you imagine that you are the only person I talk to?

This time it was the man sitting in the back who remained silent, bending the newspaper nervously. He started piercing the driver’s back with his eyes again. What an anomaly, an amazing illusion: though the uneven cobblestones made the vehicle shake terribly, the figure before him seemed to have been perfectly still, as if the driver weren’t sitting in the box seat, but levitating a quarter of an inch above it.

– I am the only one who knows for sure. Me – and you – repeated the carriage man – But such a state of affairs will not be kept for long. They have become too sure of themselves. Soon, the gossip will be spread around. I wouldn’t like to be in your shoes when noble citizens of Tomaszów start talking – a quiet giggle could be heard in the darkness.

– What is the solution then? – the passenger couldn’t take his eyes off the illusion, which played with his senses.

– Shame and injustice, injustice and shame. Do you know how it all happened? Why it happened? You must imagine that it’s because of the age difference: she is young and beautiful, and you, compared to her – old and repulsive. And because of the fact that you weren’t in the army, you were not recognised as a hero, you have not been awarded those medals you’ve dreamed of as a young boy. Perhaps I underestimated you: perhaps, deep down, you can admit in front of yourself that you are no benefactor, but a man who took advantage of the circumstances to get something you had been desiring for a long time. Who knows, maybe you even helped their happiness: acting behind her back, with the help of your friend Bornstein, you pushed her family towards their persecution, just so you could later act as the saviour. Truth or not – never mind. All of this is rubbish. Matters irrelevant, or barely consequences of the true source of your problems. Would like to know where the issue lies? I’ll tell you: s h e h a s n e v e r c o n s i d e r e d y o u a m a n. For her you are just a coward, a person without character, solely able to manipulate despicably, while sitting inside your safe office, to buy out of your problems with money, which you did not earn, but inherited. She despises you, for she thinks you don’t have the courage to look someone in the eyes while standing face to face. That’s why she adores the other one so much: she sees him as your opposite. But I know that there is not that much difference between you and him. I believe in you Sir, even if you don’t believe in yourself. We shall solve your problems, as we always do: we will mend the injustice, wash off the shame, and stop any gossiper from that disregarding talk about you.

– What should we do then? – asked the passenger, hesitating for a moment. His voice was a bit shaky, and his guts were crawling with anxiety, tickling unpleasantly in the stomach. Never before had the carriage driver talked so much about him alone. The passenger was hoping that the hunch about the forthcoming answer was misleading.

– On the seat, beside you – said the carriage driver with a cold voice.

It took a few seconds for the man to understand the meaning of the words. He reached out and located at once the only thing his eyes couldn’t see in the dark: a heavy, hard object wrapped in a black cloth, laying right under his umbrella. How was it possible that he hadn’t noticed that before?! His heart was beating fast, as he placed it in his hand.

– Unwrap it.

The blood rushed out of the passenger’s face as he opened the package. The world started spinning, and the background got blurry, as if it was painted with watercolours. There was no more street, no more city around him: just a sailboat drifting into the windless night through the ocean of darkness.

– Well, won’t you say anything, Sir? – a mocking voice rang in the man’s ears. The passenger wanted to say something, but he couldn’t make a sound: an overproduction of the saliva flooded his throat; an insanely quick pulse made him dizzy.

– I know your issue – he heard the voice again – I am quite a psychologist, I can make the right diagnosis. You are paralyzed with fear of the punishment, of consequences – as well as with the uncertainty as to whether such a drastic measure is necessary. Don’t trouble yourself with the latter, we will manage to find a stimulus able to numb this resistance. As for the dread of being punished – listen to me very carefully. The thing I’m about to tell you shall sound like a fairy tale – but do not be deceived by the sound of it. It is the honest truth, the events I’ve witnessed are just as true and reliable as everything I have told you so far about people you know in person. Besides, have I ever deceived you? Have I ever let you down? So please, shut your eyes and listen.

It all happened not so long ago, in a place not far away from here. In a certain country, small and unimportant, a cruel tyrant came to power. That happened in quite a usual fashion: in times of crisis, a group of people stepped up, promising quick and revolutionary solutions, pointing directly at the alleged wrongdoers of the nation. It was the corrupted politicians residing in the capital who were supposed to be guilty, and the unwanted unit, spreading around the homeland like a weed, like leeches sucking the life forces out of their countrymen. Driven by the wave of the societal enthusiasm, those new heralds obtained power effortlessly, by means of revolution. After that they dealt with their political opponents. But the roots of the crisis must have been growing deeper that it was thought, for it quickly turned out that the change of the authorities not only did not avert the crisis, but quite the opposite – for the crisis has deepened. When the nation noticed what was happening, people started muttering and gradually turning their backs on their self-proclaimed saviours. But those were not going to give up once taken power at all. To protect themselves from riots, they’ve built a police state, justifying it with the need for protection against saboteurs and the external enemy. In the same time, they were trying to direct society’s discontent towards the latter. The nation was enchained, but as the history showed – it wasn’t as bad as it was about to get. For the new rulers shared their power, and the competition between them somehow limited their despotic impulses. But when people got used to the new state of affairs, and the unity stopped being a necessity, the race for leadership started. In that kind of a contest there can be only one winner – and so it happened this time. Conspiracies and court intrigues, temporary alliances which would end in a traditional backstabbing. That became a routine for the local elites, and it lasted until only one player remained in the game: him. When he got powerful enough, the tyrant began a brutal combat with every possible type of opposition – the real and the imaginary one, the one in the past, in the present, and in the future. All of a sudden the authoritarianism of previous rulers seemed almost idyllic. The dictator spared no one – neither people bound to the past system, nor political and ethnic suspects. But most importantly, he exterminated all his former companions and their servants. The country was drowned in blood. Every day there was a show trial, followed by a death sentence, passed on the basis of fabricated evidences and testimonies forced by tortures. Being suspected meant being guilty. State investigators were afraid to share their victims’ faith, and so they did whatever they could to extract from the prisoners awaited self-accusations and denunciations. There was only one rule – the investigated was supposed to live long enough to point out next culprits of fake crimes. What happened with him or her after that didn’t matter. Security forces didn’t have to be told twice. In basements of prisons there were beatings, breaking of fingers, and pouring the boiling water into ears. Eventually, the tyrant ran out of people who could be a hypothetical threat to his rule. One thing was left on his list: to take care of those who committed murders on his behalf. After all, it wouldn’t be wise to make the undercover police feel t o o needed. Every man can be replaced: and so the old executioners themselves were put in torture chambers, paying for the atrocities committed by command of their leader, making place for the next generation of torturers. But the latter didn’t survive for long as well: soon they met the faith of their predecessors. And so the fiend sat down on his throne and celebrated his power.

Dark times began for the country, marked by an awful suffering. Absurd decrees, issued through ignorance or caprice, led to famine, and to the ruin of the land. The only ones who avoided the harshness of the new order were protégés of the ruler: individuals lacking any moral fibre, standing above the law, whose only duty was to tremble at the very sight of the tyrant. And when all seemed lost – suddenly an incident happened, which lit up the hope in people’s hearts.

There was a man in his prime, who came from a poor family of labourers. The local folks considered him a saint. He was famous for his wisdom and kindness, and so many people, even those living far, far away, came to him for advice. Although he himself was poor as a church mouse, he would share the last loaf of bread with anyone in need. Sometimes he could foresee the future, therefore many people took him for a prophet. His fame was spreading around, and so eventually the words reached the tyrant. The dictator, whether he feared the opponent, or got jealous of the crowd’s sincere love, decided to assassinate the old man – but, as it was in his habit, he was not very subtle about it. The arrest was made under the accusation of a public hate speech against the authorities. When the dictator’s henchmen dragged the man out of the cottage, in presence of the crowd of onlookers ( which were inattentively allowed to watch the incident), the sage got into a trance, cursed the fiend and foretold his doom.

“Soon a day shall come, when the nature itself will rebel against the tyrant,” shouted the man, “On that day thunders will bring the dark clouds, not the other way around. With a clear blue sky, there will be one hundred and fifty crashes of a thunder, and the sun will hide behind the dark fog, which shall bring the white hail. And the ground shall shake under people’s feet. Then, the hero will emerge from the crowd, and – with the help of heavenly powers – he will punish the fiend severely.”

The old man died an horrible death, but his martyrdom only strengthened his status of the saint, and the message of the prophecy spread around the country like disease. Although it was being mercilessly exterminated by the Security Force, it was thriving under roofs of households, circling around in secret. All the people looked forward to the day of the prophecy – even the dictator, gradually swamped by his age, loneliness and the burden of committed crimes, would from time to time mention words of the sage and wait for the signs, all concerned.

A few years later, when the enthusiasm evoked by the old man’s story had already curbed, one summer’s day, by the order of the tyrant the nation gathered at the biggest town square in the capital to take part in the obligatory celebration of the ruler’s birthday. The sky was perfectly clear, the weather beautiful, and it was at least a thousand degrees in the sun. The despot, along with his family and the closest henchmen, sat down in the very centre, in the biggest lodge, surrounded by an army of guards. The culmination of the parade was supposed to consist of fifty six shots from a special cannon, for that was the age of the tyrant. Though lacking originality, it was a new idea, for some reason introduced only this year. And when gunners started to fire, a very peculiar event occurred. Black dots, multiplying horrendously fast, appeared above the heads of the crowd. Everyone knew instantly what was really happening. Years ago, at the beginning of his rule, the dictator had a whim to bring and settle in capital’s parks a rare breed of a huge, black bird from overseas. The newcomers have adapted even too well, for they quickly dominated other species, not accustomed to such kind of competition, and spread uncontrollably, becoming a true plague in the city. Now countless swarms of those birds, frightened by the lengthy cannonade, started flying up to the sky, and their enormous wings covered the sun almost completely. Circling above the heads of people, they started defecating, dropping a hail of faeces on the crowd. Then the onlookers understood. The tyrant understood as well – and he froze on his throne, able to neither speak nor move. Everyone stood as one, counting shots from the cannon. When the fifty-fifth shot was fired, there was a sudden silence, for the staff couldn’t finish the cannonade because of a technical problem. And so, the shiver of excitation and terror ran through the gathered. The last sign was awaited. And indeed, the ground shook under their feet. It was nothing but a mild earthquake: a phenomenon last witnessed here a hundred years ago. What happened in people’s hearts was indescribable – I know it, because I’ve been there. The excitement almost blew their heads off. Some of them were looking for an angel of justice, stepping down from the sky covered with black wings. Others searched around the square for the long-awaited hero. And those who were standing close enough to see what was happening in the ruler’s lodge, enjoyed the expression of fear on the tyrant’s face, his trembling for the forthcoming revenge and punishment. Everyone froze, thrilled, looking forward impatiently to what was about to happened. And do you know what happened then?

– What? – asked the passenger, hypnotised by the driver’s story. He didn’t even notice that the carriage hadn’t been moving for some time now, and that the street on which they were now was the one to have streetlamps.

– I’ll tell you, If you haven’t figured it out yet: a b s o l u t e l y n o t h i n g. The earth eventually stopped shaking, and the birds stopped circling. Or maybe I expressed myself wrong: nothing expected by the crowd happened. For when the dictator shook off the shock, he got down to business right away. First, he shot his eldest son. In many versions of the ever-evolving legend he was the one to avenge the country. Then he ordered his guards to shoot the first row of people gathered behind the fence, just in case, to prevent possible “heroes of men” from stepping up. This led to regular riots initiated by the feverish crowd. In response to that, Security Forces opened fire. That day went down in history as the Bloody Saturday on the Central Square. When the dust came down, and the fire from the rifles ended, those who survived dragged their relatives’ corpses home, all covered in blood and birds’ shit. The tyrant, in turn, came back safely to his fortress, where he lived and ruled for the next ten years, till the day when he died of natural causes – in sleep, laying in his own bed. Then his stream of consciousness was cut off, and his buried body eaten by worms, just as it happened to thousands of his victims during this bloody rule.

After such a long story the carriage driver stopped talking and stretched himself out in the box seat. For a little while there was an absolute silence: it had stopped raining some time ago, horses weren’t snorting, and the carriage, now standing still, became completely mute. All of this woke the man up. The blinders were taken off his eyes, and so he finally looked around: they were on św. Tekla street, outside his own house. In spite of such a late hour, the familiar windows were full of light – that sight make him shiver to the bone, and filled his guts with liquid fire.

– You are not wrong: it’s your bedroom – the driver went on, poisoning the passenger with his voice – They are this blatant, they despise you this much. Despite all your money and connections you are nothing but a trash to them, a zero. They’re afraid of nothing, for they think that even if you caught them red-handed, you would do nothing about it. That for fear of scandal you would just close your eyes and pretend not to see them. Just as you would later cover your ears and pretend not to hear the gossip and the mockery. That is their opinion about you. Their – not mine. I brought you here in this particular moment because I know that deep down you’re different. I’ve told you my story to teach you a lesson. And so, there are two conclusions. First of all: there is no other compensation for your injustice than the one you should be able to enforce. Second of all: you will never be punished, neither here, nor in the eternal life, unless you allow it through your own weakness. So now take what I gave you and go there to show both them and me what you’re made of.”

The passenger stood up, and the bended issue of “The Echo of Masovia” fell off his knees. In his hand there was the black package which he found on the seat. He moved as if he wanted to leave the carriage, but he froze halfway. His eyes were piercing the back of the driver’s head.

– Come with me, please – he whispered.

– I a m n o t h i n g m o r e t h a n a c a r r i a g e d r i v e r – the voice answered slowly, stressing every word – I help people get where they want to be, but I cannot enter their houses. Don’t be afraid, everything will go down well. It’s just a matter of strong will.

The passenger was still in the carriage. Touched by a new desire, he started squirming and moving around, so that he could finally look his driver in the eyes. His efforts came to nothing, for the figure seemed to be cloaked in an everlasting shadow. the man then straightened up, and his body froze, as a new alarming thought crossed his mind.

– W h a t m a k e s y o u t h i n k t h a t y o u a r e s o m e h o w e x c e p t i o n a l ? D o y o u i m a g i n e t h a t y o u a r e t h e o n l y p e r s o n I t a l k t o? – he repeated the carriage driver’s words like an echo – So it was because of you that young Mitzner…

– Go now, hurry up! – the poisonous voice drown out his own, interrupting in the middle of the sentence – you are right: my hearing is excellent. Right now I can hear you wife moaning, and her lover growling. I’ve also got a perfect sense of smell: the scent of her body, the stink of his sweat, the odour the jacket, soaked in the cigarettes’ smoke, thrown on the floor reached me from the distance. Your marriage bed is creaking and pounding against the wall. Servants pretend to be deaf, but if you don’t hurry up, then the little Adaś, your son from the previous marriage, will soon wake up and start peeking through the keyhole. I wonder what will be your explanation, if he ever asks you about what he saw.

A screechy laugh could be heard in the air.

The passenger squeezed the black object, opened the door of the carriage and ran out into the night.

July, 2017

Marcin Wiśniewski

The carriage driver of Tomaszów

Tomaszów Mazowiecki – November, 1926

Autumn, as usual, brought nothing but rain and sleet. Jan Kalita put up the collar of his tattered coat and rubbed his hands. He got off his box seat for a moment and snuggled into Bay’s mane. He and the horse belonged to each other, needed each other. That is why they were bound by a great friendship. Bay shook his head, breathing out steamy air through his nostrils, warming up the freezing face of the carriage driver for a little while. Jan petted his muzzle and scratched the horse’s moist back.

– Another rainy day – he thought. It was almost seven o’clock, and his regular client was just about to emerge from the gate – director Rychter. The man had been driving him twice a day, ever since Mr Ksawery became one of the directors of the Synthetic Fibre Factory in Tomaszow Mazowiecki.

Jan did not own a watch, but some inner clock was telling him that seven o’clock had already passed, and Director Rychter was never late. Suddenly he saw Mrs Rychter and the five-year-old Amelia leaving the outbuilding. The mother and the daughter, like two peas in a pod, went up to the carriage. Jan jumped off the box seat, took off his cap and gave a deep bow. He knew Mrs Matylda Rychter well, for he sometimes drove her and Miss Amelia to her father, to Rzeźnicza street. The woman caught the driver’s hand, and, squeezing gently his strong, roughened by work palm, said quietly:

– Jan, There is a chest in the living room. Would you fetch it, please? Then we shall go to my father – her voice was so quiet that in the first moment the carriage driver did not fully understand the message, but he quickly pulled himself together and went to the outbuilding.

The door were slightly opened, so he entered and started looking around the rooms, listening to the silence. His look was curious, and somewhat astonished, for he had never seen such an apartment. His thoughts were disturbed by the striking of the clock standing in the living room. It was chiming a quarter past seven, and it scared Jan so much that he almost turned a somersault, tripping over the chest. He took the luggage promptly, though it was heavy and unhandy. The driver threw it into the carriage, where both clients were already sitting. Little Amelia was shaking from cold, or, perhaps, from something else.

– Mrs Matylda, there is a warm blanket under the seat, lets cover the young lady. It is awfully cold today, and it will be raining soon, for certain. Mrs Rychter glanced at Jan gratefully with her sad, blue eyes. The girl cuddled herself with the warm rug and fell asleep. Bay went down the pavement, and after some reflection Jan decided to ask:

– Did Director Rychter have to go somewhere? – the silence was his first answer, but after a while he heard Mrs Matylda’s soft voice:

– Yes Jan, he was called to go to Łódź. He is signing some industrialist’s documents – she explained.

Jan did not ask again, for it was not his affair. He drove up to Rzeźnicza street, fetched the heavy chest and carried sleeping Miss Rychter inside the tenement, where she was taken by her nanny. Mr Witebski, Mrs Matylda’s father, went out and welcomed his daughter as soon as the carriage arrived in front of the house. There was a deep silence accompanying, and Jan felt that his heart ached, for some great sorrow overwhelmed his soul. Mrs Rychter squeezed his hand for the second time that day, and he felt warmth, in spite of the silky gloves she was wearing.

– You are a good man Jan, thank you – she said, sliding a few Polish marks into his hand. Jan gave a deep bow, holding the money in one hand, and his cap in the other, which he already managed to take off. The man turned around, got up on his box seat and drove away. A slight drizzle began sprinkling from the sky, and soon the raindrops became bigger and bigger, bumping loudly onto the carriage roof. Jan drove back to św. Antoni street, gave the horse a bit of hay to eat, and sat inside the carriage to protect himself from the rain. There was a blanket on the floor, the same one covering Miss Amelia during the ride. He picked it up, folded and put it back in its place.

Being in the throes of the busy day, the carriage driver was slowly forgetting morning events. Hardly had he driven home for the evening, when his beloved daughter, Lidka, threw her hands around his neck. His wife’s strict voice rang out from the kitchen:

– Leave your father alone, he is tired after work, let him wash up and sit down for the super – her voice got warmer and Jan knew that she was not angry with their daughter, for she was the apple of her father’s eye. He changed many things in his life for her, and she as well brought him great happiness. Being one of the best students in the Merchants Association Gymnasium of Humanities, she adored her beloved papa, as she would call him. The daughter waited for the carriage driver to finish eating, so she could tell him latest news from the town, and learn even more from him. Scarcely had he given back his plate, kissing his wife’s forehead and hand thankfully, when she sat down on a little stool and started talking:

– Papa – said she, staring at him with her brown eyes, and for a moment Jan saw the blue, sad glare of Mrs Rychter. He shook off the nagging thoughts and listened to his daughter’s tales. Lidka talked about school, about Baśka, whose brother got a job as a messenger in the “Tomaszów Courier”, and many other matters. Jan kept listening, and when she finished, he stood up and started putting on his jacket.

– What do you think you’re doing, walking around the streets at night? – Mrs Kalita was deeply concerned, ready to cover the door with her own body if she had to. Twenty years had passed since she became Jan’s wife, and although upon Lidka’s birth sixteen year ago, Jan took an oath before Saint Mary in the Saint Anthony Church that he shall no longer drink, and so far he would have kept his promise, the fear that her husband might go back to drinking still flickered in Ms Kalita’s soul.

– Easy, my love. I’m just going to check up on Bay. He got soaking wet during the road, and he cannot see the pavement clearly anymore. It’s because of that new lightning. There was no problem with the gas one – until the carriages were rolling, you were sure that the lamplighter would never put out the lights. Now those electric street lamps are switched off before even I get to the stable.

He was telling the truth, but he also wanted to be with his own thoughts for a while. Jan carried a distress in his heart, and every time he shut his eyes, he would see Mrs Rychter’s face. At night he couldn’t sleep as well, and before the sun rose, he was sitting at the table, drinking the morning coffee.

– What’s wrong with you; you can’t sleep? – Mrs Kalita stood behind him, all concerned. Jan buried his head in her warmed up by sleep body, and felt peaceful again. He didn’t want to worry her with his nightmares, so he just smiled and said in a calm voice:

– I am leaving earlier today, it’s not raining; maybe there will be more clients. People always want to go somewhere when there’s a nice weather.

He smiled, and went off to work in a better mood. The weather indeed created perfect conditions for work. And since it was Saturday, there were even more clients after dinner, for although a fortnight already has passed since the All Souls’ Day, a lot of folks still wanted to go the cemetery, lit up a candle on their family graves. Something tempted Jan in the evening, and so he drove to Rzeźnicza street. Lurking through the window, all he saw was a tiny light. Sitting in the box seat full of reverie, he heard a voice behind him:

– Are you free?

All of a sudden Jan felt cold, so he put up his coat collar higher.

– And where would you like to go, kind Sir? – asked the driver, tightening the reins.

– The Police Headquarters downtown, but it has to be fast – uttered the firm voice, and so the carriage made its way towards św. Józef street. But Jan was curious why this man was in Mr Witebski’s tenement, so he casually started the conversation:

– Sir, have you seen the town hall rising? Folks keep talking that it will be all nice and good for use with the end of winter – Jan went on, talking about the gas lighting, which has been in town for five years, and about new contracts with Dutchmen in the factory, but the client was not talkative much, and so the driver ran out of topics very quickly. Deep down he was thanking God for such a smart daughter, because it was her who brought him all the news from school, or read it in the newspaper. They reached their destination, and Jan moved towards home, for it got dark and it was already Bay’s mealtime. At home two things waited for him: a warm nourishment and his daughter, who, ignoring mother’s reprimand about letting her father eat in peace and not wittering on, for they had to get ready for the mass next day morning, sat at the table and waited. Jan understood his wife well. He had been sitting in the carriage all week, while people smoked cigars, sometimes wreaking of booze, and there was also Bay’s odour accompanying. He had to wash off all of it, so that he could be clean and dignified for church in the morning. But Lidka was not giving up. Hardly had her mother disappeared behind the stove, when she put the latest issue of the newspaper in front of her father:

– Look papa, look what happened in town! – she was almost screaming.

Jan looked at the “Tomaszów Courier”, where huge letters read: “ DIRECTOR’s BODY FOUND ON THE BANKS OF PILICA”. With his hand over the plate, he looked at the headline and muttered:

“Quickly dear, read the whole thing.”

Lidka picked up the paper, all proud that it was her who brought the news:

– Yesterday morning, Mr Antoni S. found a travel trunk while walking along the Pilica river. Led by curiosity, he came closer and almost breathed his last, as next to the trunk a body was lying…

Jan stopped listening, his face got pale, his eyes turned red, and he felt heart attack or another heartburn coming. Taking a deep breath, the driver stood up.

– What’s wrong papa? Did you know this director? – Lidka was concerned.

– Oh dear, your dad was driving this Rychter man every day to his work in the factory – her mother explained, giving Jan a glass a cold water. Thankful for the water, and the explanation, the man put on his coat and left. But this time Mrs Kalita did not stand in his way, for even if he wanted to go for a drink, she would have forgiven him, after all it was an atrocity, what happened. But Jan did not go to the pub. He went to the church. Kneeling at the altar, the driver hid the head in his arms and cried bitterly.

… 20 years later

– Maybe it was for the best that you didn’t go with me to the cemetery dear. It’s been five year since father passed away, and it’s still difficult – Mrs Kalita stroke her daughter’s hair. She took pride in her child, for Lidka graduated from all the schools, even during the war she would be running for special faculties. She served as a nurse during the Uprising, providing assistance, and now she was a wife, mother, and a doctor.

– Your father would be proud my love – the women were coming back from the cemetery towards the tenement, which endured the wrath of war. Behind them there were Stefan and Jan Kordecki walking. The engineer, Lidka’s husband and her 4-year-old son, who was named after his grandfather.

– Mother, what should happen with the carriage? It lasted the war in the yard. Bay is long gone. It cannot fall into ruin like this. Perhaps we should give it away for the junk yard. I know it reminds you of father, but doctor Zarębski in apartment three wants to buy a car, and needs to keep it somewhere.

She started the topic, knowing what a hard decision it will be for her mother. Father had been a carriage driver his whole life, and took great care of his vehicle. It was there that his heart stopped, and if it weren’t for Bay, who knew his way back home, who knows where he might have been found. It was a harsh year, a middle of warfare. Lidka was pregnant, Stefan was sent to the front. It was really hard. But they survived, and so the time came to bring some matters to an end.

– But first we shall clean it up, I have not look inside it since father died, perhaps there is something which should be kept at home.

Much to her daughter’s delight, Hanna made the right decision. The war has ended a year ago, it was time for new beginnings. They went straight to the yard.

– Grandma – asked little Jan – was grandpa driving anyone important in his carriage?

– Plenty, plenty of important and famous folks, but also common people of Tomaszów. He was driving them to work, to church, for weddings and christenings, and sometimes he would accompany them on their last journey to the cemetery. Everybody knew and respected him, as he respected them, treating every folk equally.

Hanna Kalita gave her grandson a deep hug.

– Son, come inside, look under the seats, maybe there are some things we should throw out, so that we don’t embarrass ourselves at the junkyard, this carriage is famous around here, everybody will know to whom it belongs.

Mrs Kalita started cleaning the vehicle. Jan obeyed his grandmother, and as he was little, he fit under the sofas easily. The boy found an old cigar, a piece of a newspaper and some candy wrapper. But there was no treasure, only an old blanket:

– Grandma, what should I do with this old rug? – he asked, dragging it with him. Suddenly everyone heard a distinct, metallic sound, as if something hit the ground. Stefan took his son away from the blanket.

There was a knife on the ground, big, sharp, with a wooden grip.

– Why did grandpa have this knife? – asked the boy.

Lidka came to her mother:

– Take him to the house, please – she whispered, picking up the tool through the handkerchief .

– Dear? – asked Stefan, looking at his wife with concern. – Everything alright?

– Stefan, there’s blood on this knife, dried, but I’m sure that it’s blood – said the woman quietly, wrapping it back in the blanket. They both looked at each other. A sudden wind stirred the papers found by little Jan. The letters on the 20-year-old newspaper read:

“DIRECTOR’S BODY FOUND ON THE BANKS OF PILICA”.

Who killed the director? Was it all just an accident? What role did Jan Kalita play in all of that? Will his daughter, or perhaps his grandson discover the truth?

Dominika Zdulska

Where the sun bids the Horizon farewell

Stranger’s steps. A few blunt strokes of a hammer and a sharp sound of breaking the wet from the evening rain glass. Dead silence.

Streets of the city loved such exquisite concerts. For the past month they had become an extraordinary Sunday tradition. Every time, between nine o’clock and midnight, every single performance was virtually identical – variations on the subject of the broken glass, accompanied by the sound of wooden bats or hammers. Sometimes enriched with the rhythmical noise of a getaway, and even more seldom – but only once in a blue moon – with muffled screams of the musicians soaked in their own artistic ecstasy, trying to enhance their work with a bigger exposition of feelings. Those nationalists. The city loved them – modernistic virtuosos, making the biggest effort to be heard by all their fellow citizens. Every night was a true feast for body and soul.

Hieronim also loved listening to such a romantic sound of broken glass. And though he visited the Warsaw Philharmonic only once, as a twelve-year-old boy, his knowledge of music was extraordinary. Had it not been for the old piano inherited after his long-gone aunt, he would have most probably become like hundreds of other boys from Tomaszów – an ordinary, dull individual, doomed to work in the factory. As an amateur pianist, Hieronim placed great value on the contribution of the local nationalists to the artistic development of the city. After all, Tomaszów was swamped with labourers, and labourers – as his father, who devoted most of his life to work in the synthetic fibre factory, used to say – had no time for such nonsense as music. It’s the hard work that counts. You have to feed your family, maintain your house. And money comes as an effect of that murderous struggle, politely called ‘work’. This everlasting, destructive chase after the coin destroys a human soul. Of that Hieronim was sure. And a man without a soul cannot create. Which, as the young music lover imagined, indicated that nationalists must have been particularly spiritual. A man without a soul becomes a worthless, empty box. And that was exactly how he pictured hell – being placed in a horrible manufacture or another factory, where all people can think about is how to survive for the pennies they get. Let alone the fact that factory owners weren’t generous at all. At least not those from Tomaszów.

Apparently, the sky enjoyed its practical jokes, because all of a sudden, there was a pouring rain. A blue umbrella shot up rapidly, like a bullet. The full head of blond hair, which would eventually get frizzy, mostly because of Ingrid, already caught the humid air, which made Hieronim look like a soaked stray cat, rather than a lion with a sophisticatedly bushy mane. Ah, Ingrid. The boy lost all of the enthusiasm just thinking about her. He stopped in the dark gate of some tenement, took out the cigarette and lit it up. Standing silently, he got his blank glance stuck in the wall, analysing everything. So it’s today. Hieronim felt numb, and every thought going through his head came with unbelievable difficulties. He bit his lip. It was his old habit in the face of an enormous, forthcoming wave of stress. He put out the rest of the cigarette with his shoe, and, despite his better judgment, moved confidently towards the route leading to the suburbs. It was almost nine, and summer nights allowed for being late. The boy saw a small figure in the distance. It was her.

She was much more elegant than usually. Her long, dark hair was styled in an original, low bun. She must have been wearing her best dress, and the beads on her neck were shiny blue. The light frill waved in the wind, making Ingrid even more charming. Standing there, in the middle of the country path, she looked like some kind of a Slavic goddess, blessing the fields for an abundant harvest. The pale skin of this German girl was quite a contrast to the dark background of the woods. In her hand there was an umbrella, already closed. The rain has just stopped, and the beautiful scent of raindrops was everywhere. The cool wind stroke her cheeks, which was both refreshing and disturbing. Hieronim glanced away, just as the girl threw arms around his neck. He didn’t want to look her in the eyes. He knew what he would see. Fear and tears which can’t be wiped away, even with the kindest words. The boy felt as if he was in some kind of a play, with one difference – the stage here was his life, and he and Ingrid both served as protagonists. Tragic heroes. Whatever they would do, it would end in failure. He felt that the grip became tighter. With a shaky voice, Hieronim whispered:

“ I will never forget about you. But really, it’s for your own good. It’s dangerous here, you know that. There are rumours about a war. It will be better out there. I will write to you every day, I promise.”

Then there was silence. The German girl let go of the boy and wiped away the tears. She looked him deeply in the eyes, and saw that he was just as devastated as her. Admiring him as if he was a piece of art, Ingrid tried to remember every tiniest detail of his looks. She touched his cheek with a warm, light hand. It was cold. The blond hair has already got soaking wet, and there were single raindrops on the shirt, the reminder of the bad weather. Here, east of Germany, her home, she is made to abandon her dreams. There, where the sun bids the horizon farewell, her broken, aching heart will lie forever. So this is the God’s way. Why, why would he invite her to the paradise, just to banish her so brutally? What did she do to deserve this?

“I don’t want any letters,” said she in a lowered voice, squeezing his hand nervously,

“I want to stay here. This whole Stuttgart, it’s a curse.”

“You can’t. I won’t allow it. I won’t allow anyone or anything hurt you,” responded Hieronim, relatively calm,” Distance doesn’t matter. I will always find you, I am even ready to move to Germany. I heard that ‘to love’ means as much as ‘being ready to suffer’”.

…

“Who’s there?”

“It’s Adam Michalec.”

Heavy, slightly old-fashioned door moved with a sound indicating that they were oiled up at least ten years ago. Behind them, in the half-light, there was a man, probably in his prime, nagging the soaked guest inside. His hands were wrapped around a paraffin lamp, gleaming in the dark. He led the guest to a room looking like a cabinet. The prevalent stuffy smell, enriched by the cigarette smoke present in almost every corner, was choking and itchy for the throat. It was not an ideal atmosphere for serious talks, taking into account the peculiar hour and circumstances. The host put down the lamp and looked suspiciously at the young lad. The latter was oddly calm, observing gigantic deer horns, which hung proudly on the wall. After some time the man, hiding his nervousness ineffectively, asked:

“What brings you here, at such late hour?”

The lad, sitting down in a red chair, took a deep breath and said:

“ I’ve got something that should be very interesting for you.”

The eyes of the youngster gleamed with something the host deemed disturbing.

“Have you heard the name Wenzlaff before?” asked Adam, looking his interlocutor straight in the eyes.

“Of course I have. They are the German owners of a few shops, as I think. Wealthy people. But what does that have to do with anything? Cut to the chase.”

A trace of an ironic smile played across the guest’s lips. He took the picture out of his leather bag. There were a couple with a small, maybe four-year-old girl in a carriage. The boy threw it rudelyon the host’s desk. The latter, getting more and more confused, requested clarification. All of a sudden the ironic smile vanished. With a deadly serious face and an awfully cold voice, Adam announced harshly:

“It appears, Mr Wyszkowski, that you’ve got an exceptionally treacherous and shrewd scum in your organization.”

“What do you mean?”

“It seems like our Hieronim is not that exemplary, model even nationalist and activist you took him for. What a disappointment! Who knew that the man so devoted to his nation from the earliest years would suddenly start secretly collaborating with the German rats, in such a vile manner…”

Wyszkowski held his breath. His hands went numb, his face got sweaty. Could Hieronim really be a traitor? Him? That couldn’t be true. The boy came from a noble, loyal to nationalism family of labourers. No one could say anything bad about the Wołyniak family, they were respectable people. Since his thirteenth birthday their son had been a keen volunteer, and contributed greatly to spreading the idea of nationalism. He was much like his father. They both put their country on the pedestal. The young Wołyniak was the last person the man would suspect of being a traitor on such a great scale. Wyszkowski put out his cigarette nervously, sinking into his own dark thoughts. For a while he was hoping that all this was just a bad, cruel joke, made up by some bored boys. It was true that some time ago someone told him that Hieronim was an item with the Wenzlaff’s daughter, but the boy promptly denied all the accusations. One of the recently approved members of the organization claimed to have seen them together, hastening to the outskirts of the city. But it was not in Adam’s nature to joke. He looked very maturely for his age. Wyszkowski trusted the young man.

“This has to be some kind of a mistake. I know Hieronim and his family very well,” he said quietly, trying to seem calm.

“I’ve got a proof. Look carefully at the photo. The young Ingrid Wenzlaff had lately lost her husband, a German officer. She was left with her four-year-old daughter. The widow’s father took her to Tomaszów. They’ve got a beautiful estate in the suburbs. And Hieronim is a dirty liar, the photos and the folks’ talk will confirm it. He deceived us all. And you put such great trust in him. Now everyone knows the truth. I caught the lovely couple red-handed. I have men and guns. Traitors must be exterminated. Literally. This shall be a warning for other betrayers.”

…

The streets of Tomaszów suburbs had completely vanished in the thick, obscure darkness of the night. Only the pale moon, hiding itself behind the clouds, allowed to find some guidance in the dark. The cold wind made the body shiver. In the distance one could hear dogs bark. It reminded Hieronim of a loud quarrel between the neighbours. Now every sound ached him like a knife’s blade. He was walking slowly, looking in the distance. An enormous pain was piercing his body. The boy felt his heart break rapidly. His whole world, built so intricately, was lost. He still believed that all of this was just a bad dream. That Ingrid was not leaving, and tomorrow she would endow him with her beautiful smile. Hieronim treated every day spent with his beloved as if it was his last. He knew very well that others would try to destroy their love. Without her, he was just an empty box – because it was her who brought life to his soul. And now he lost her. And the love, and the soul. It was the folks’ hatred that took her away. It was people who banished her from his life, who made her run. They hunted her and took away his happiness, and he pursued it for so long. But no war, no hatred shall kill this love. He would fight for it at all costs, even at a cost of his own life. God was watching over him, that he believed. And that this whole evil was just a transition. And that at the end of this long wander, there was a promised land waiting. Love does not know the word ‘death’.

A might blast of shot bullets carried over the trees.

Darkness.

The sound of a body falling with a hollow sound on the ground got to Adam’s ears after a while.

Mission accomplished.

Matzevot

Spaces of Memory Foundation was informed that there is a Jewish tombstone built into the local pavement. The Foundation has already made an effort to take the tombstone on its proper place that is Jewish cemetery. Thank you very much for the information and keep watching all the traces of old Tomaszów.

Farewell

We are deeply saddened by the news of Mrs. Halina Czapiga passing. She was a friend of the Spaces of Memory Foundation. Dear Mrs. Halinka, thank You very much for Your smile and Your stories. We are so grateful that You introduced us to Your family archives and to Your spaces of memory. We promise to take care of those archives and to remember. See You!

THANKS TO DONORS

Spaces of Memory Foundation would like to thank to all persons who have donated to the project Metamorphoses of the City. This a very significant gesture for us and let us say thank you so much! Thanks not olny to the donors below, but also to those who decided to stay anonymous.

Bożena z Tomaszowa Mazowieckiego, Przemysław Biernat, Justyna Chądzyńska, Mieczysława Gajek, Robert Garczyński z Tomaszowa Mazowieckiego, Paweł Herzog – artysta fotograf, Wojciech Kaczor – urzędnik, Maria Ka – Kawska, Natalia Kiełpińska, Tomasz Kowalski, Aleksandra Kulis, Jadwiga Mach, Anna Małodzińska, Michalina Mieszczankowska, Monika, Renata Radzikowska, grupa nieformalna Sanae Feminae, Karol Sienkiewicz, Beata Siła-Młynarczyk, Gabriela Stefańczyk-Wlazło – kierownik Biura Projektów UM, Kamil Szczepanik, Piotr Szczepanik, Tomek z Tomaszowa, Maksymilian Wroniszewski, Anna Zwardoń

SHOLEM ALEICHEM!

Last Friday on 10th of July there was a Jewish Culture Festival in Tomaszów Mazowiecki. The Spaces of Memory Foundation with Geniusz Creative Education had a great pleasure to lead workshop GIMEL-SHIN. The participants of the workshop painted dreidels which had been made for us by Bartłomiej Sęk, Damian Kafar and Daniel Szafrański. Thank you so much for being with us and for sharing that common, green space of culture at Barlickiego 26/28 street. Take a look at the pictures and remember the rules of our game: NUN (nischt, nothing), GIMEL (ganc, take all), HEI (halb, half), SHIN (sthel, put down). A sheinem dank!

- Mir (we)

- Shin un hei (Shin and hei)

- Shin, gimel un shin (Shin, gimel and shin)

- Un vos iz dos? (And what’s that?)

- Mir (we)

- Di kinderlech (children)

- Un dos iz gimel! (And that’s gimel!)

- Dos iz shin! (This is shin!)

METAMORPHOSES OF THE CITY

Spaces of Memory Foundation would like to run a project Metamorphoses of the City and that is why is asking you for your support. To run the project we need 10,000 PLN and we have been already searching for donation by crowdfunding platform. Please, find the English translation of the project below. For all donators and supporters we have gifts.

https://polakpotrafi.pl/projekt/metamorfozy-miasta

Spaces of Memory Foundation would like to invite you to a phantasmagoric journey around the old, non-existent any more, multicultural city of Tomaszów Mazowiecki. The Foundation wishes to create a theatrical tale narrated by the movements of puppets and by creative, unlimited imagination attempting to animate archive materials.

Metamorphoses of the city is a theatrical project aiming to re-establish the rhythm of pre-war Tomaszów, where languages of four different cultures reverberated: Polish, German, Russian and Jewish. The project will consist of series of workshops leading to the creation of puppetry performance. Raised funds will be designated for: fees for the workshop leaders, musical composition, film and photographic documentation of the project and the performance, translation of the tale, materials for the photographies and stage set, promotional activities and administrative and organizational costs. Fourteen-day project will take place at the beginning of August, and free workshops will be available for everyone aged over 13. The performance will be presented to the audience during several evenings.

We would like to invite you to become a patron, a creator or a spectator of our puppet follies!

DRAMATURGY

During drama workshops we will create a tale about old Tomaszów, referring to folk tales, legends and memories of the citizens of Tomaszów. We will develop narrative concept and the gallery of characters. We will sharp our literary and critical sense, we will learn to think by colour and shape to meet the requirements of a puppet theatre.

Justyna Biernat is a Ph.D. student at the Jagiellonian University. She graduated from Theatre and Drama Studies as well as Classics. She was undertaking research towards her Ph.D. at the University of Oxford under the supervision of Professor Oliver Taplin. She is a reviewer for Polish theatre journals, tutor of classes on modern theatre performances for students and drama classes instructor for children. Recently, she has been preparing research “Publishing and critical edition of Letters from the ghetto of Tomaszów Mazowiecki”. Tomaszów Mazowiecki is her home town.

PUPPETRY

During the puppetry workshops we will create the protagonists of our tale and learn different ways of making puppets with the use of paper, wood and fabric. Once the puppets are prepared we will learn how to manipulate them: we will prepare control bars, we will attach the puppets and learn to control the load.

Ewa Maria Wolska is a student of the Academy of Dramatic Art in Warsaw, the Department of Puppet – Theatre Art in Białystok. She graduated from culture studies and Polish philology at the University of Łódź. She is a scholar of the President of Białystok, she led many puppetry workshops for children and youth in Poland and abroad. She worked as a theatre artisan (making of stage sets and costumes) in „Arlekin” Theatre in Łódź.

MUSIC

Our tale will be passed on to the musicians of Agnellus band. They will create music for our performance referring to the tale. By means of their voice and sound they will lead puppets, or maybe the puppets will lead and inspire them. During our performances we will listen to live music.

Agnellus performs music situated between alternative and poetic rock with jazz and folk elements. In 2012 the group released album „Ballads and trances” with modernist and contemporary poetry of artists of Łódź. Recently Agnellus has prepared the album „Ball for poor” and made project „Wyliczanki, igry, fiki” – a musical interpretation of popular word games for children.

We encourage and invite you to participate in our tale!

Let’s meet in its unreal world!

GIFTS:

We have gifts for our supporters and the gift depends on the amount of donation.

10 PLN or more = You will receive a personal e-postcard via email. We will thank You by Facebook as well.

25 PLN or more = You will receive a postcard with the image of old Tomaszów and a bookmark with our thanks. We will thank You by Facebook as well.

35 PLN = You will receive a poster of our production with our thanks. We will thank You by Facebook as well.

50 PLN = You will receive: recording of our production, a postcard with the image od old Tomaszów, a bookmark with our thanks. We will thank You by Facebook as well.

75 PLN = You will receive: recording of our production, a postcard with the image od old Tomaszów, a bookmark with our thanks. You will also get the originally designed bag with the image of old Tomaszów. We will thank You by Facebook as well.

100 PLN = We thank You at our Website. You will receive: recording of our production (with English subtitles), a bookmark, postcard and originally designed bag with the image of old Tomaszów.

200 PLN = We thank You at our Website. You will receive recording of our production (with English subtitles), originally designed bag with the image of old Tomaszów and a pendant made by our puppeteer.

300 PLN = We thank You at our Website as well as in the recording of our production. You will receive recording of our production (with English subtitles), originally designed bag with the image of old Tomaszów, postcards with the image of old Tomaszów. You will receive a tale with dedication from all authors of the project/production. Moreover, you will receive a pendant made by our puppeteer and a gift-surprise.

500 PLN = You will receive the honorary title: Donor of Spaces of Memory. You will receive recording of our production (with English subtitles) and a tale with dedication from all authors of the project/production. Moreover, you will receive a pendant made by our puppeteer, originally designed bag with the image of old Tomaszów and a poster of the production. Your Name or the logo of Your Company will be seen at our Website and in the recording of the production with the note that You are the Donor of Spaces of Memory. You will also receive a gift-surprise.

LETTERS FROM THE GHETTO

On December 10th 2015 the Informal Group “Tomaszów’s Dramatists” presented the performative reading of drama “Letters from the ghetto” in Teresa Gabrysiewicz-Krzysztofik Municipal Public Library in Tomaszów Mazowiecki. The play was written by participants of the dramatists’ workshop whithin the project “Non/Memory. Theatre in Tomaszów Mazowiecki” and consists almost solely of letters from the ghetto of Tomaszów. Izrael Aljuche Orenbach, the author of letters, born in Tomaszów, was a resident of the ghetto. During the period from the winter of 1939 until the winter of 1941, he maintained a lively correspondence with his beloved girl Edith Blau.

The performative reading was presented by: Weronika Biernat, Przemysław Biernat, Wiktoria Kondejewska, Anna Kowalska, Krzysztof Karbowiak, Hanna Sęk and Bartłomiej Sęk under the supervision of Justyna Biernat. They performed also in Municipal Public Library in Opoczno on December 11th. The play will be published in the journal “Arterie” as well as translated into English. The Group would like to thank to US Holocaust Memorial Museum and Julian and Irena Tuwim Foundation for the permission to read and publish the drama. Many thanks to Maria Ka who supported us with her music. We recommend her website: https://mariaka.bandcamp.com/

- Esterka’s House that is Municipal Public Library in Opoczno

- Orenbachs (Krzysztof Karbowiak, Anna Kowalska) dancing

- after the performative reading

- Lutek (Przemysław Biernat) and Henryk Barczyński (Bartłomiej Sęk)

- Municipal Public Library in Tomaszów. actors-amateurs

- still reading

- Szeps, head of Jewish Council (Krzysztof Karbowiak) and Fred, Lutek’s cousin (Weronika Biernat)

- Socrates’ scene (poem by Julian Tuwim was included in the drama)

- conversation (Justyna Biernat and guests)

“Cigarette Mamma” sang by Maria Ka was an important component of the drama reading.